David Merrick

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2022) |

David Merrick | |

|---|---|

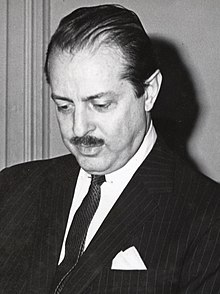

Merrick in 1962 | |

| Born | November 27, 1911 |

| Died | April 25, 2000 (aged 88) London, England |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Washington University in St. Louis Saint Louis University School of Law |

| Occupation | Theatrical producer |

| Spouse(s) | Leonore Beck (m. 1938; div. 1963) Jeanne Gibson (m. 1963; div. 1966) Etan Aronson (m. 1969; div. 1976; m. 1983; div. 1999) Karen Prunczik (m. 1982; div. 1983) Natalie Ting Teresa Lloyd (m. 1999 - 2000 his death) |

| Children | 2 |

David Merrick (born David Lee Margulois; November 27, 1911 – April 25, 2000) was an American theatrical producer who won a number of Tony Awards.

Life and career

[edit]Born David Lee Margulois to Jewish parents in St. Louis, Missouri, Merrick graduated from Washington University in St. Louis, then studied law at the Jesuit-run Saint Louis University School of Law.[1] In 1940, he left his legal career to become a successful theatrical producer.

His first seven productions were hits, starting with Clutterbuck in 1949, which he produced in partnership with Irving Jacobs, and he set a precedent in 1958 of having four productions on Broadway simultaneously; all hits: Look Back in Anger, Romanoff and Juliet, Jamaica and The Entertainer.[2] He often was his own competition for the Tony Award, and he frequently won multiple nominations and/or wins in the same season.

Merrick was known for his love of publicity stunts. In 1949, his comedy Clutterbuck was running out of steam, but along with discount tickets, he paged hotel bars and restaurants around Manhattan during cocktail hour for a "fictive Mr. Clutterbuck" as a way of generating name recognition for his production, and it helped his show keep alive for another few months.[3] Another famous stunt promoted the poorly reviewed 1961 musical Subways Are For Sleeping. Merrick found seven New Yorkers who had the same names as the city's seven leading theater critics: Howard Taubman, Walter Kerr, John Chapman, John McClain, Richard Watts Jr., Norman Nadel, and Robert Coleman. Merrick invited the seven namesakes to the musical and secured their permission to use their names and pictures in an advertisement alongside quotes such as "One of the few great musical comedies of the last thirty years" and "A fabulous musical. I love it." Merrick then prepared a newspaper ad featuring the namesakes' rave reviews under the heading "7 Out of 7 Are Ecstatically Unanimous About Subways Are For Sleeping". Only one newspaper, the New York Herald Tribune, published the ad, and only in one edition; however, the publicity that the ad garnered helped the musical remain open for 205 performances (almost six months). Merrick later revealed that he had conceived the ad several years previously, but had not been able to execute it until Brooks Atkinson retired as The New York Times theater critic in 1960 since he could not find anyone with the same name.[4]

Merrick joined The Lambs in 1950, and in 1968 he joined the board of directors of the Riviera, a hotel and casino on the Las Vegas Strip in Las Vegas, Nevada, alongside Harvey Silbert and Harry A. Goodman.[5] He also worked with director and choreographer Gower Champion, who directed Merrick's production of 42nd Street. But on the morning of August 25, 1980, Champion died of a rare blood cancer, and Merrick announced the news himself to both the cast and the audience at the opening night curtain call.

Merrick suffered a stroke in 1983, after which he spent most of his time in a wheelchair. He established the David Merrick Arts Foundation in 1998 to support the development of American musicals.

Personal life

[edit]Merrick was married six times to five women.

His first marriage was to fellow native-St. Louisan Leonore Beck. They married January 16, 1938,[6] and divorced on January 11, 1963.[7]

His second wife, Jeanne Gibson, was a Kentucky-born Broadway press agent. They met at the Savoy Hotel in London, where Gibson was working as the hotel’s press consultant.[8] She became pregnant in 1962, while Merrick was still married to Beck.[9] Their daughter, Cecilia Ann Merrick, was born January 1963.[10] Gibson and Merrick were married from spring 1963 until October 1966.[11]

He married Etan Aronson (February 24, 1944 - July 26, 2023),[12] a Swedish model and former flight attendant, twice. They first married in September 1969, and divorced in Mexico three weeks later,[13] but the divorce was not finalized in America until 1976.[14] Together, they had a daughter, Marguerita Merrick (born September 1972).[15]

On July 1, 1982, Merrick married actor Karen Prunczik,[16] who originated the role of Anytime Annie and filled in for a week playing the lead character Peggy Sawyer in Merrick’s 42nd Street. They divorced in 1983.[17]

Merrick and Aronson married for the second time on Tuesday, August 30, 1983 in Greenwich, Connecticut.[18] In the late 1980s, they adopted two children, Olivia Merrick (born May 1988) and Carl Christian Merrick (born July 1987),[19] although in 1994 Merrick petitioned the court to cancel the adoption.[20] Merrick and Aronson divorced again in October 1999, after lengthy divorce proceedings.[21]

Merrick met Natalie Lloyd (born Natalie Ting Teresa in Shanghai in 1954) in the late 1980s when she was working as a receptionist in the office of William Goodstein, Merrick’s lawyer.[22] They started living together almost immediately, while Merrick was still married to Aronson. Merrick and Lloyd married November 1999, less than six months before Merrick’s death on April 25, 2000.[23]

Honors

[edit]In 1965, Merrick received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[24]

In 2001, Merrick was inducted into the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[25]

Biography

[edit]An unauthorized biography by Howard Kissel is titled David Merrick: The Abominable Showman (ISBN 978-1-55783-361-7).

Cultural references

[edit]In "What Does A Naked Lady Say to You?", a first-season episode of The Odd Couple, the director of the nude off-Broadway play Bathtub (itself based on Oh! Calcutta!) complains after police officer Murray Greschler (Al Molinaro) busts the production for indecency, "Murray, you wouldn't do this to me if I was David Merrick!"

In "We Closed in Minneapolis", a first-season episode of The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Mary's character comments to the mailroom guy upon seeing his delivery to Murray's desk of what she assumes to be a rejection letter, "Oh, poor Murray. He's been writing this play for three years. You'd think Broadway producers would be sensitive enough to do more than just stick mimeographed rejection slips in when they send it back. You know, something like a nice, handwritten note saying, "Good work, Murray. Nice try. Love, David Merrick."

Quotes

[edit]- "It's not enough that I should succeed, others should fail." (This statement has also been attributed to François de La Rochefoucauld, Gore Vidal, and Genghis Khan.)[26]

Awards and nominations

[edit]- 1958 Tony Award for Best Play (Romanoff and Juliet, nominee)

- 1958 Tony Award for Best Play (Look Back in Anger, nominee)

- 1958 Tony Award for Best Musical (Jamaica, nominee)

- 1959 Tony Award for Best Play (Epitaph for George Dillon, nominee)

- 1959 Tony Award for Best Musical (La Plume de Ma Tante, nominee)

- 1960 Tony Award for Best Musical (Take Me Along, nominee)

- 1961 Special Tony Award (winner)

- 1961 Tony Award for Best Play (Becket, winner)

- 1961 Tony Award for Best Musical (Do Re Mi, nominee)

- 1961 Tony Award for Best Musical (Irma La Douce, nominee)

- 1962 Tony Award for Best Producer of a Play (Ross, nominee)

- 1962 Tony Award for Best Producer of a Musical (Carnival, nominee)

- 1962 Tony Award for Best Musical (Carnival, nominee)

- 1963 Tony Award for Best Producer of a Musical (Oliver!, nominee)

- 1963 Tony Award for Best Musical (Oliver!, nominee)

- 1963 Tony Award for Best Musical (Stop the World – I Want to Get Off, nominee)

- 1964 Tony Award for Best Producer (Musical) (Hello, Dolly!, winner)

- 1964 Tony Award for Best Play (Luther, winner)

- 1964 Tony Award for Best Musical (Hello, Dolly!, winner)

- 1965 Tony Award for Best Producer of a Musical (The Roar of the Greasepaint – The Smell of the Crowd, nominee)

- 1965 Tony Award for Best Musical (Oh, What a Lovely War!, nominee)

- 1966 Tony Award for Best Play (Inadmissible Evidence, nominee)

- 1966 Tony Award for Best Play (Philadelphia, Here I Come!, nominee)

- 1966 Tony Award for Best Play (Marat/Sade, winner)

- 1967 Tony Award for Best Musical (I Do! I Do!, nominee)

- 1968 Special Tony Award (winner)

- 1968 Tony Award for Best Producer of a Play (Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, winner)

- 1968 Tony Award for Best Play (Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, winner)

- 1968 Tony Award for Best Musical (The Happy Time, nominee)

- 1968 Tony Award for Best Musical (How Now, Dow Jones, nominee)

- 1969 Tony Award for Best Musical (Promises, Promises, nominee)

- 1970 Tony Award for Best Play (Child's Play, nominee)

- 1971 Tony Award for Best Play (The Philanthropist, nominee)

- 1972 Tony Award for Best Play (Vivat! Vivat Regina!, nominee)

- 1973 Tony Award for Best Musical (Sugar, nominee)

- 1975 Tony Award for Best Musical (Mack & Mabel, nominee)

- 1976 Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Revival (Very Good Eddie, nominee)

- 1976 Tony Award for Best Play (Travesties, winner)

- 1981 Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Musical (42nd Street, nominee)

- 1981 Tony Award for Best Musical (42nd Street, winner)

- 1986 Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Revival (Loot, nominee)

- 1986 Tony Award for Best Reproduction (Loot, nominee)

Additional notable stage productions

[edit]- Clutterbuck (1949)

- Fanny (1954)

- The Matchmaker (1955)

- Look Back in Anger (1957)

- Romanoff and Juliet (1957)

- Jamaica (1957)

- The Entertainer (1958)

- The World of Suzie Wong (1958)

- La Plume de Ma Tante (1958)

- Destry Rides Again (1959)

- Gypsy (1959)

- Take Me Along (1959)

- Irma La Douce (1960)

- A Taste of Honey (1960)

- Becket (1960)

- Do Re Mi (1960)

- Carnival! (1961)

- Subways Are For Sleeping (1961)

- I Can Get It for You Wholesale (1962)

- Stop the World – I Want to Get Off (1962)

- Oliver! (1963)

- Luther (1963)

- 110 in the Shade (1963)

- One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1963)

- The Milk Train Doesn't Stop Here Anymore (1964)

- Hello, Dolly! (1964)

- Foxy (1964)

- Oh, What a Lovely War! (1964)

- The Roar of the Greasepaint – The Smell of the Crowd (1965)

- Pickwick (1965)

- Cactus Flower (1965)

- Marat/Sade (1965)

- Don't Drink the Water (1966)

- I Do! I Do! (1966)

- Breakfast at Tiffany's (1966)

- Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead (1967)

- How Now, Dow Jones (1967)

- The Seven Descents of Myrtle (1968)

- The Happy Time (1968)

- Promises, Promises (1968)

- Forty Carats (1968)

- Play It Again, Sam (1969)

- Private Lives (1969)

- Mack and Mabel (1974)

- Very Good Eddie (1975)

- State Fair (1996)

Film productions

[edit]Merrick produced four films:

- Child's Play (1972)

- The Great Gatsby (1974)

- Semi-Tough (1977)

- Rough Cut (1980)

References

[edit]- ^ "David Merrick". The Official Masterworks Broadway Site. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ "'Jamaica' Nears Payoff, Will Give Merrick 4-Hit B'way Grand Slam". Variety. March 19, 1958. p. 1. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- ^ "David Merrick, 88, Showman Who Ruled Broadway, Dies". The New York Times. April 27, 2000. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

Mr. Merrick kept it alive for six months with discount tickets and a publicity stunt:

- ^ Museum of Hoaxes.com; "A 4-Star Smash? Says Who?", Miami News, January 6, 1962, p. 4A

- ^ "Merrick a Vegas Investor". Kansas City Times. May 13, 1968. p. 2. Retrieved August 18, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kissel, Howard (1993). David Merrick, the abominable showman : the unauthorized biography. New York. p. 47. ISBN 1-55783-172-6. OCLC 28800530.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kissel, Howard (1993). David Merrick, the abominable showman : the unauthorized biography. New York. p. 252. ISBN 1-55783-172-6. OCLC 28800530.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kissel, Howard (1993). David Merrick, the abominable showman : the unauthorized biography. New York. p. 189. ISBN 1-55783-172-6. OCLC 28800530.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kissel, Howard (1993). David Merrick, the abominable showman : the unauthorized biography. New York. p. 244. ISBN 1-55783-172-6. OCLC 28800530.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kissel, Howard (1993). David Merrick, the abominable showman : the unauthorized biography. New York. p. 251. ISBN 1-55783-172-6. OCLC 28800530.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "The Boston Globe 08 Oct 1968, page 2". Newspapers.com. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ "ETAN MERRICK Obituary (2023) - New York, NY - New York Times". Legacy.com. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- ^ Kissel, Howard (1993). David Merrick, the abominable showman : the unauthorized biography. New York. p. 399. ISBN 1-55783-172-6. OCLC 28800530.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Arizona Daily Sun 04 Sep 1983, page 8". Newspapers.com. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ Kissel, Howard (1993). David Merrick, the abominable showman : the unauthorized biography. New York. p. 437. ISBN 1-55783-172-6. OCLC 28800530.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kissel, Howard (1993). David Merrick, the abominable showman : the unauthorized biography. New York. p. 460. ISBN 1-55783-172-6. OCLC 28800530.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Karen Prunczik – Broadway Cast & Staff | IBDB". www.ibdb.com. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ "Arizona Daily Sun 04 Sep 1983, page 8". Newspapers.com. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ Kissel, Howard (1993). David Merrick, the abominable showman : the unauthorized biography. New York. p. 482. ISBN 1-55783-172-6. OCLC 28800530.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Newsday (Suffolk Edition) 25 Mar 1994, page 8". Newspapers.com. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ "Daily News 27 Oct 1999, page 32". Newspapers.com. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ Kissel, Howard (1993). David Merrick, the abominable showman : the unauthorized biography. New York. p. 484. ISBN 1-55783-172-6. OCLC 28800530.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Omaha World-Herald 26 Apr 2000, page 2". Newspapers.com. Retrieved December 19, 2022.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ St. Louis Walk of Fame. "St. Louis Walk of Fame Inductees". stlouiswalkoffame.org. Archived from the original on October 31, 2012. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ "It Is Not Enough to Succeed; One's Best Friend Must Fail". quoteinvestigator.com. August 6, 2012. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

External links

[edit]| Archives at | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| How to use archival material |

- 1911 births

- 2000 deaths

- 20th-century American Jews

- American theatre directors

- American theatre managers and producers

- American entertainment industry businesspeople

- Broadway theatre producers

- Businesspeople from St. Louis

- Missouri Democrats

- New York (state) Democrats

- Tony Award winners

- Washington University in St. Louis alumni

- Saint Louis University School of Law alumni

- 20th-century American businesspeople

- American casino industry businesspeople

- American corporate directors

- Special Tony Award recipients