Horace Porter

Horace Porter | |

|---|---|

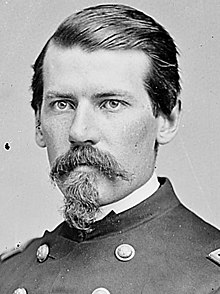

Porter in the 1860s | |

| United States Ambassador to France | |

| In office May 26, 1897 – May 2, 1905 | |

| President | William McKinley Theodore Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | James B. Eustis |

| Succeeded by | Robert S. McCormick |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 15, 1837 Huntingdon, Pennsylvania, US |

| Died | May 29, 1921 (aged 84) Manhattan, New York, US |

| Resting place | West Long Branch, New Jersey, US |

| Spouse |

Sophie King McHarg

(m. 1863; died 1903) |

| Relations | Andrew Porter (cousin) Andrew Porter (grandfather) George Bryan Porter (uncle) James M. Porter (uncle) |

| Children | 4 |

| Parent(s) | David Rittenhouse Porter Josephine McDermott |

| Education | Lawrenceville School Harvard University |

| Alma mater | West Point |

| Occupation | Soldier, author, President of the Union League Club of New York |

| Awards | Medal of Honor Legion of Honor |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States Union |

| Branch/service | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1860–1873 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | |

Horace C. Porter[1] (April 15, 1837 – May 29, 1921) was an American soldier and diplomat who served as a lieutenant colonel, ordnance officer and staff officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War, personal secretary to General and President Ulysses S. Grant. He also was secretary to General William T. Sherman, vice president of the Pullman Palace Car Company and U.S. Ambassador to France from 1897 to 1905.[2]

Early life

[edit]

Porter was born in Huntingdon, Pennsylvania, on April 15, 1837,[3] the son of David Rittenhouse Porter (1788–1867), an ironmaster who later served as Governor of Pennsylvania, and Josephine McDermott.

His paternal grandfather was Andrew Porter, the Revolutionary War officer and his paternal uncles included George Bryan Porter, the Territorial Governor of Michigan, and James Madison Porter, the Secretary of War. Among his first cousins was Andrew Porter, a Mexican–American War veteran and Union Army brigadier general.[3] His aunt, Elizabeth Porter, was the grandmother of Mary Todd Lincoln.[4]

Porter was educated at The Lawrenceville School in Lawrenceville, New Jersey (class of 1856)[5] and Harvard University.[6] He graduated from West Point July 1, 1860.[3]

Career

[edit]Porter was commissioned a second lieutenant on April 22, 1861, and a first lieutenant on June 7, 1861.[3] During the American Civil War, Porter served in the Union Army, reaching the grade of lieutenant colonel by the end of the war.[3]

During the war, he served as chief of ordnance in the Army of the Potomac, Department of the Ohio and the Army of the Cumberland.[3] He was distinguished in the Battle of Fort Pulaski, Georgia, at the Battle of Chickamauga, the Battle of the Wilderness and the Second Battle of Ream's Station (New Market Heights).[3] On June 26, 1902, or July 8, 1902,[7] Porter received the Medal of Honor for the Battle of Chickamauga as detailed in the citation noted below. In the last year of the war, he served on the staff of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, later writing a lively memoir of the experience, Campaigning With Grant (1897).[3][8]

From April 4, 1864, to July 25, 1866, Porter was aide-de-camp to General Ulysses S. Grant with the grade of lieutenant colonel in the regular army.[3] On July 17, 1866, President Andrew Johnson nominated Porter for appointment as brevet brigadier general, to rank from March 13, 1866, and the U.S. Senate confirmed the appointment on July 23, 1866.[9] From July 25, 1866, to March 4, 1869, Porter was aide-de-camp to General Ulysses S. Grant with the grade of colonel in the regular army.[3]

Grant administration

[edit]

From 1869 to 1872, Porter served as President Grant's personal secretary in the White House. At the same time, he held the grade of colonel and an appointment as aide-de-camp to General William T. Sherman.[3]

Porter had refused to take a $500,000 vested interest bribe from Jay Gould, a Wall Street financier, in the Black Friday gold market scam. He told Grant about Gould's attempted bribery, thus warning Grant about Gould's intention of cornering the gold market. However, during the Whiskey Ring trials in 1876, Treasury Solicitor Bluford Wilson claimed that Porter was involved with the scandal.[10][11] Porter testified before the committee investigating the scandal and was never formally charged with wrongdoing.[12] Porter resigned from the U.S. Army on December 31, 1873.[3]

Later life

[edit]After resigning from the Army, Porter became vice president of the Pullman Palace Car Company, and later, president of the West Shore Railroad. He was U.S. Ambassador to France from 1897 to 1905,[3] paying for the recovery of the body of John Paul Jones and sending it to the United States for re-burial. He received the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor from the French government in 1904. In addition to Campaigning with Grant, he also wrote West Point Life (1866).[2]

Porter was president of the Union League Club of New York from 1893 to 1897. In that capacity, he was a major force in the construction of Grant's Tomb.[2]

He was elected an honorary member of the Pennsylvania Society of the Cincinnati in 1902. He was also a member of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, the Sons of the American Revolution and a Hereditary Companion of the Military Order of Foreign Wars by right of his descent from Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Porter who served in the American Revolution.[2]

In 1891 he joined the Empire State Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, where he served as President General from 1892 through 1896. He was assigned national membership number 4069 and state membership number 69.[13]

He died in Manhattan, New York and is interred at the Old First Methodist Church Cemetery in West Long Branch, New Jersey.[14]

Personal life

[edit]In 1863, Porter was married to Sophie King McHarg (1840–1903),[8] the daughter of John McHarg (1813–1884) and Martha Whipple Patch.[15] Together, they were the parents of:[8]

- Horace Porter Jr., who died at the age of 23 of typhoid fever.

- Clarence Porter, who died after the first World War.

- Elsie Porter, who married Edwin Mende of Berne, Switzerland.[16]

- William Porter, who died in infancy.

After a period of suffering,[16] Porter died at New York, New York, May 29, 1921.[3][2] He was buried in West Long Branch Cemetery, West Long Branch, New Jersey.[3][17] In his will, he left the Grant Association $10,000 and the flag that flew at General Grant's field headquarters during the Civil War.[18]

Medal of Honor citation

[edit]

Rank and Organization:

- Captain, Ordnance Department, U.S. Army. Place and date: At Chickamauga, Ga., September 20, 1863. Entered service at: Harrisburgh, Pa. Born: April 15, 1837, Huntington, Pa. Date of issue: July 8, 1902.

Citation:

- While acting as a volunteer aide, at a critical moment when the lines were broken, rallied enough fugitives to hold the ground under heavy fire long enough to effect the escape of wagon trains and batteries.[19]

See also

[edit]- List of American Civil War Medal of Honor recipients: M–P

- List of American Civil War brevet generals (Union)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Dunkelman, Mark H. (June 12, 2006). "Lieutenant Colonel Horace C. Porter: Eyewitness to the Surrender at Appomattox". historynet.com. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "HORACE PORTER". The New York Times. 30 May 1921. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3. pp. 435–436

- ^ Evans, W. A. (2010). Mrs. Abraham Lincoln: A Study of Her Personality and Her Influence on Lincoln. SIU Press. ISBN 9780809385607. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ Eicher, 2001, p. 435 identifies this as the Lawrence Scientific School.

- ^ "GEN. PORTER RECALLS SCHOOL DAYS OF '54; Lawrenceville Alumni Honor Him at Waldorf Banquet. BIG CHANGE IN FIFTY YEARS No Broken Heads Then in Football and Baseball Was "Towball" -- Woodrow Wilson on Athletics". The New York Times. 25 March 1906. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ The uncertainty as to the date is expressed in the source, Eicher, 2001, p. 435

- ^ a b c "McHarg Family Papers: Part 2". findingaids.library.georgetown.edu. Georgetown University Archival Resources | Georgetown University Manuscripts. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ Eicher, 2001, p. 736

- ^ Jean Edward Smith, Grant, pp. 481-490, Simon & Schuster, 2001.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 409

- ^ New York Times, Western Whisky Frauds: Gen. Horace Porter's Testimony, August 13, 1876

- ^ "Presidents General of the SAR and Annual Congress Sites". Sons of the American Revolution website. 2014-03-18. Archived from the original on 2011-10-26. Retrieved 2015-02-19.

- ^ Long Branch in the Golden Age

- ^ "MRS, HORACE PORTER DEAD; Wife of American Ambassador to France Expires Suddenly. A Chill Develops Into Congestion of the Lungs--Gen. Porter Prostrated--American Colony in Paris Shocked". The New York Times. 7 April 1903. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ a b "GEN. HORACE PORTER NEAR DEATH AT HOME; Ex-Ambassador to France, 84 Years Old, Is Suffering From a General Breakdown". The New York Times. 27 May 1921. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "NOTED MEN AT BIER OF GENERAL PORTER; Hear 'Taps' Soundsd Over Veteran at Simple Services in 5thAv. Presbyterian Church.DEEDS PRAISED IN PRAYER Rev. Dr. John Kelman Gives Thanksfor "One of the Great Gentlemen of the Olden Days."". The New York Times. 3 June 1921. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "MANY PORTER HEIRS GET LARGE ESTATE; Battle Flag of Grant, Now in Tomb, Left to Upkeep Association With $10,000 Bequest". The New York Times. 10 June 1921. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "PORTER, HORACE, Civil War Medal of Honor recipient". American Civil War website. 2007-11-08. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

References

[edit]- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- McFeely, William S. Grant: A Biography (1981).

- "Civil War Medal of Honor recipients (M-Z)". Medal of Honor citations. United States Army Center of Military History. August 3, 2009. Archived from the original on February 23, 2009. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

Further reading

[edit]- Modern Eloquence: Vol III, After-Dinner Speeches P-Z at Project Gutenberg, contains a number of speeches by Porter.

- Mende, Elsie Porter; Henry Greenleaf Pearson (1927). An American Soldier and Diplomat, Horace Porter. Frederick A. Stokes Company.

- Owens, Richard Henry (2002). Biography of General and Ambassador Horace Porter, 1837-1921: Vigilance and Virtue. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-7734-7242-8.

- Porter, Horace. Campaigning With Grant. New York: The Century Co., 1897. Time-Life Books reprint 1981. ISBN 0-8094-4202-7. (deluxe)

External links

[edit]- Works by Horace Porter at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- 1837 births

- 1921 deaths

- Ambassadors of the United States to France

- American Civil War recipients of the Medal of Honor

- Grant administration personnel

- Harvard University alumni

- People from Huntingdon, Pennsylvania

- People of Pennsylvania in the American Civil War

- Personal secretaries to the President of the United States

- Porter family

- Union army colonels

- United States Army officers

- United States Army Medal of Honor recipients

- United States Military Academy alumni

- Lawrenceville School alumni

- Presidents General of the Sons of the American Revolution