Carlos Mesa

Carlos Mesa | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 2004 | |

| 63rd President of Bolivia | |

| In office 17 October 2003 – 9 June 2005 | |

| Vice President | Vacant |

| Preceded by | Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada |

| Succeeded by | Eduardo Rodríguez Veltzé |

| 37th Vice President of Bolivia | |

| In office 6 August 2002 – 17 October 2003 | |

| President | Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada |

| Preceded by | Jorge Quiroga |

| Succeeded by | Álvaro García Linera |

| Leader of Civic Community | |

| Assumed office 13 November 2018 | |

| Preceded by | Alliance established |

| Official Representative of Bolivia for the Maritime Claim | |

| In office 28 April 2014 – 1 October 2018[a] | |

| President | Evo Morales |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Position dissolved |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Carlos Diego de Mesa Gisbert 12 August 1953 La Paz, Bolivia |

| Political party | Revolutionary Left Front (2018–present) |

| Other political affiliations | Independent (before 2018) |

| Spouses | Patricia Flores Soto

(m. 1975; div. 1978)Elvira Salinas Gamarra

(m. 1980) |

| Children |

|

| Parents | |

| Education |

|

| Alma mater | |

| Occupation |

|

| Awards | List of awards and honors |

| Signature |  |

| Website | |

Carlos Diego de Mesa Gisbert[b] (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈkaɾlos ˈðjeɣo ˈmesa xisˈβeɾt] ; born 12 August 1953) is a Bolivian historian, journalist, and politician who served as the 63rd president of Bolivia from 2003 to 2005. As an independent politician, he had previously served as the 37th vice president of Bolivia from 2002 to 2003 under Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada and was the international spokesman for Bolivia's lawsuit against Chile in the International Court of Justice from 2014 to 2018. A member of the Revolutionary Left Front, he has served as leader of Civic Community, the largest opposition parliamentary group in Bolivia, since 2018.

Born in La Paz, Mesa began a twenty-three-year-long journalistic career after graduating from university. He rose to national fame in 1983 as the host of De Cerca, in which he interviewed prominent figures of Bolivian political and cultural life. His popular appeal led former president Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada of the Revolutionary Nationalist Movement (MNR) to invite him to be his running mate in the 2002 presidential election. Though Mesa's moderate left-wing sympathies contrasted with centre-right policies of the MNR, he accepted the offer, running as an independent in a hotly contested electoral campaign. The Sánchez de Lozada-Mesa ticket won the election, and, on 6 August, Mesa took charge of a largely ceremonial office that carried with it few formal powers save for guaranteeing the constitutional line of succession. Shortly into his term, conflict between Sánchez de Lozada and Mesa arose. By October 2003, the increasingly tense situation surrounding the ongoing gas conflict caused a definitive break in relations between the president and vice president, leading the latter to announce his withdrawal from government after clashes between protesters and military personnel led to several deaths. Crucially, Mesa opted not to resign from his vice-presidential post and succeeded to the presidency upon Sánchez de Lozada's resignation.

Mesa assumed office with broadly popular civic support but leading a government without a party base and devoid of organic parliamentary support left him with little room to maneuver as his public policy proposals were severely restricted by the legislature—controlled by traditional parties and increasingly organized regional and social movements spearheaded by the cocalero activist and future president Evo Morales. As promised, he held a national referendum on gas which passed with high margins on all five counts. Nonetheless, widespread dissatisfaction resurged, and his call for a binding referendum on autonomies and the convocation of a constituent assembly to reform the Constitution failed to quell unrest. Mesa resigned in June 2005, though not before ensuring that the heads of the two legislative chambers renounced their succession rights, facilitating the assumption of the non-partisan Supreme Court judge Eduardo Rodríguez Veltzé to the presidency. With that, Mesa withdrew from active politics and returned his focus to various media projects and journalistic endeavors. In 2014, despite previous animosity, President Evo Morales appointed him as the international spokesman for the country's maritime lawsuit against Chile before the International Court of Justice (ICJ), a position he held until the final ruling at The Hague in 2018.

Mesa's work for the maritime cause propelled him back into the national consciousness, and he soon emerged as a viable alternative to Morales as a contender for the presidency, even surpassing the president in electoral preference polls. Shortly after the ruling by the ICJ, Mesa announced his presidential candidacy. In the 2019 election, Mesa was defeated by Morales, who failed to garner a majority but won a wide enough plurality to avoid a runoff. However, irregularities in the preliminary vote tally prompted Mesa to denounce electoral fraud and call for mass demonstrations, ultimately ending in Morales' resignation and an ensuing political crisis. The following year, snap elections were held, but numerous postponements and an unpopular transitional government hampered Mesa's campaign, resulting in a first-round loss to Movement for Socialism (MAS) candidate Luis Arce. Mesa emerged from the election as the head of the largest opposition bloc in a legislature that does not hold a MAS supermajority for the first time in over a decade.

Early life and career

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]

Carlos Mesa was born on 12 August 1953 in La Paz.[3] Through his father, José de Mesa, he is of Spanish descent; his grandfather, José Mesa Sánchez, emigrated to Bolivia from Alcalá la Real in 1910. Due to his heritage, in 2005, the city's council unanimously designated Mesa as the adoptive son of the municipality.[4] His mother, Teresa Gisbert, was of Catalan descent; her father and mother emigrated from Barcelona and Alicante.[5] Together, de Mesa and Gisbert were two of the most prominent Bolivian architects, historians, and museologists of their time.[6] He has three younger siblings: Andrés, Isabel, and Teresa Guiomar.[7]

Between 1959 and 1970, Mesa completed primary and began secondary studies at the all-boys private Catholic and Jesuit San Calixto School in the Següencoma barrio of La Paz.[8] In 1970, he traveled abroad to Spain, completing his high school education at the San Estanislao de Kotska School in Madrid. After graduating, Mesa entered the Complutense University of Madrid, pursuing majors in political science and letters. After three years, he returned to Bolivia, where he enrolled in the Higher University of San Andrés (UMSA), graduating with a degree in literature in 1978.[9] During his stay there, in 1974, he directed the UMSA's Faculty of Humanities magazine.[10]

At the age of twenty-two, Mesa married Patricia Flores Soto, though they divorced three years later. Two years after that, on 28 March 1980, he married Elvira Salinas Gamarra, a psychologist and environmental consultant with whom he has two children: Borja Ignacio and Guiomar.[11]

Journalistic career

[edit]Film critic and archivist

[edit]On 12 July 1976, while still a student of the UMSA, Mesa, along with Pedro Susz and Amalia de Gallardo, helped found the Bolivian Cinematheque. With the support of Renzo Cotta of the Center of Cinematographic Orientation and La Paz Mayor Mario Mercado, the group secured a small amount of space on the fifth floor of the La Paz House of Culture in order to start their film archive. The first addition to the collection was a short film directed by Jorge Ruiz Laredo about the violinist Jaime Laredo, which was donated by the pianist Raúl Barragán.[12] Along with Susz, Mesa served as the cinematheque's executive director from its foundation until 1985, remaining a member of its board of directors after that.[10]

Radio host and producer

[edit]Mesa's first foray into radio occurred in 1969, concomitantly his first journalistic endeavor. Through his father, he secured a three-month internship for Radio Universo, where he would haul portable tape recorders to ministerial press conferences before returning and cutting the recorded material for broadcast use. In 1974, with the help of Universo head Lorenzo Carri, Mesa became the independent producer and host of a program on Radio Méndez. After a brief return to Universo in 1976, Mesa moved on to Radio Metropolitana, where, together with Roberto Melogno, he produced the morning newscast 25 Minutos en el Mundo. In 1979, Mesa's meager cinematheque salary pushed him to seek more dedicated journalistic work. Together with Carri, he joined Radio Cristal, owned by Mario Castro. The pair's presentational style evolved from simple news coverage to commentary and analysis and, finally, opinion journalism. Abruptly shuttered by the military government of Luis García Meza, the station was reopened after his fall and, between 1982 and 1985, had grown to become the country's top news network.[13]

Television presenter

[edit]After a brief stint as sub-director of the evening periodical Última Hora between 1982 and 1983, Mesa made his first television debut. In that period, the only major competition to state outlets came from university television. Channel 13 Televisión Universitaria (TVU), directed by Luis González Quintanilla, played a particularly important role in the country's political process. In 1982, amid the country's democratic transition and the reopening of independent media, González invited Mesa to a panel on one of TVU's programs. Impressed by the young journalist, González called on him to take charge of a culture-themed talk show. Though Diálogos en Vivo ran for only three months, it proved to be the basis for what later became the program that spotlighted Mesa as a national television personality.[14]

The name of that program came to be known as De Cerca. The concept of the show—formulated by Bolivian National Television officials Julio Barragán and Carlos Soria—combined formal interviews of Bolivian political figures with a section in which recorded questions from ordinary citizens were relayed by the host to the guest. In mid-1983, Mesa was called on to host the show, an offer he "accepted without question". De Cerca premiered on 15 September 1983, with Minister of Planning Roberto Jordan Pando as its first guest. The show premiered at a time of a severe hyperinflation crisis in the country; Mesa's salary frequently spent long periods through the bureaucracy of the Ministry of Finance, often being delivered two or three months late. His final payment from the company, delivered in July 1985, totaled b$63.5 million due to inflation.[15]

Save for the eventual removal of prerecorded questions, which Mesa stated "broke the continuity of the program, and also limited the topic of the conversation to excessively circumstantial issues", the style and presentation of De Cerca remained largely unchanged for two decades and between four channels, lending it a sense of "permanence in time". Throughout its run, the program spotlighted a large majority of the most relevant political actors of the period; to be invited onto the show eventually became a mark of national prominence. Of those interviewed included every president of the country who governed during the show's run, as well as some prior ones, with the exception of Víctor Paz Estenssoro and Hernán Siles Zuazo, neither of whom, with few exceptions, ever accepted invitations to any television program. For Mesa, the omission of these two figures was "a great void in De Cerca that I will never finish regretting".[16]

Foundation of PAT

[edit]

On 1 August 1990, Mesa, together with fellow journalists Mario Espinoza and Amalia Pando and financially assisted by Ximena Valdivia, launched Associated Journalists Television (Periodistas Asociados Televisión; PAT). The concept of the network, then an audiovisual production company, came from the hope of establishing a newscast free of government oversight and censors. Starting from 15 September, PAT began broadcasting public news coverage to the country. In 1992, the government of Jaime Paz Zamora closed the State television company in favor of a contract with PAT, ratified by the succeeding government of Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada. Despite the State's financial support, Mesa's team of journalists took great care to maintain a level of objectivity in their reporting. Responding to questions regarding bias, Pando admits that both she and Mesa supported many of the policies of Sánchez de Lozada's first term but rejects the notion that this constituted "a tie" to the government.[c]

Despite its early success, a compounding set of issues began to mount onto the channel. Viewing the newscast as an outlet for the opposition, the government of Hugo Banzer initiated a boycott. This, coupled with an economic recession and a series of well-done but largely unpopular new programs, sent PAT into a financial crisis. According to Pando, Mesa's vice-presidential candidacy had "devastating consequences" for the channel's credibility as an independent news source. In 2007, the company was sold to businessman Abdallah Daher, who thereafter sold it to Comercializadora Multimedia del Sur. Only the name remains with the original channel.[17]

Press columnist

[edit]Mesa's longest-held editorial post was as a regular contributor to the sports supplements of the morning papers Hoy, Presencia, Viva, and La Prensa; he published for these outlets between 1976 and 2002. Between 1979 and 1986, he worked as a film critic for the La Paz prints Apertura (1979), Hoy (1981–1982), and Última Hora (1983–1986). From 2010 to 2017, he remained a regular editor-at-large for the morning newspapers El Deber, El Nuevo Sur, El Potosí, Correo del Sur, La Palabra, La Patria, Los Tiempos, Página Siete, and Sol de Pando. In addition, Mesa has written columns for international outlets such as the Spanish Diario 16 and El País, the American Foreign Policy, and Germany's Der Spiegel.[10]

Vice presidency (2002–2003)

[edit]Entry into politics

[edit]As a prominent journalist in the field of politics, the prospect of actually participating in affairs of state was an option often proposed by outside voices but which Mesa—a staunch independent despite his moderate left-wing sympathies—routinely refused to consider. His first experience refusing the call to serve came in 1986 when President Paz Estenssoro invited him to be a component of his cabinet as minister of information. Despite his stated admiration of the president, Mesa declined the offer the following day, citing his perceived inadequacy to hold the position. In the ensuing years, on various occasions, Mesa declined offers by various parties to run for vice president, mayor of La Paz, or senator. In the 1993 election, then-candidate Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada had placed Mesa on a list of pre-candidates for the Revolutionary Nationalist Movement (MNR)'s vice-presidential nomination. The Aymara activist Víctor Hugo Cárdenas was ultimately chosen and elected as the country's first indigenous vice president.[18]

From no to yes: Mesa accepts

[edit]

With elections set for June 2002, the possibility of being presented as a political candidate was once again laid on Mesa. Seeking a turnaround after its electoral defeat in the 1997 general election, the MNR opted to renominate its national chief, ex-president Sánchez de Lozada, as the party's presidential candidate. For his new bid, Sánchez de Lozada surrounded his campaign with American political consultants of the Greenberg Carville Shrum (GCS) strategy group, who employed focus groups and public opinion polls to revitalize his public image.[19] In January, Mesa received a call from the ex-president asking him to meet with members of the GCS team to discuss the results of a recent poll. Mesa's suspicions that the subject of the survey would regard political candidates were confirmed when two consultants—Jeremy Rosner and Amy Webber—met him at his office at PAT, presenting the journalist with results showing him with the highest favorability among a list of a dozen national figures.[20]

For Mesa, the festering social conflicts of twenty-first-century Bolivia necessitated a political renewal: "Paz Zamora and Sánchez de Lozada were history, their political cycle had finished, and they were prolonging it artificially and unnecessarily". If he were to become a contestant in electoral politics, he reasoned, it would be under a movement of his own design and certainly not as vice president, a post he described as "the stupidest position of all ... An office with a single objective, that of succession, with few clear powers". In meetings with Sánchez de Lozada, Mesa expressed this point, emphasizing that the MNR required younger generations among its ranks and suggesting himself as a possible alternative presidential candidate, an idea that the MNR shot down due to his political and economic inexperience.[21]

Among other considerations for Mesa were the notion of ending an almost twenty-five-year career in journalism—including the abandonment of PAT—and the perceived adverse effects assuming the vice presidency would have on his family. For these reasons, on 31 January, Mesa informed Sánchez de Lozada that he would not join the ex-president as his running mate. Two days later, however, Mesa was called to one last meeting with Carlos Sánchez Berzaín, the MNR's campaign manager, who outlined three final arguments for consideration: Sánchez de Lozada was the only candidate with the capacity to alleviate the ongoing economic crisis; Mesa could not continue in his comfortable position commentating on the sidelines of politics; the MNR's campaign team considered the inclusion or exclusion of Mesa as the deciding factor in the party's electoral outcome. It was either "with me or with me ... [and] everything else was a disaster". These points renewed doubts in Mesa, who, ultimately, apprehensively accepted the invitation just a day before the National Convention of the MNR was set to announce its presidential binomial.[22]

The PAT factor

[edit]According to Mauricio Balcázar—former minister and son-in-law to Sánchez de Lozada—the MNR paid Mesa over US$800,000 in ten installments between the 2002 campaign and October 2003 in exchange for his vice-presidential candidacy. As alleged by Balcázar, on the day of the MNR Convention, Mesa demanded the payment and an initial guarantee check of US$200,000 for his television channel PAT, threatening to withdraw his nomination if the party did not comply. For Balcázar, this constituted "extortion"—although he did not realize it at the time—because the MNR had no time to seek an alternative candidate.[23][d] An investigation carried out by analyst Carlos Valverde uncovered documents proving deposits totaling Bs6 million (US$831,454) into the bank account of PAT starting in mid-2002 and ending in October 2003. A majority of the transactions were recorded as loans to PAT by the Itaca company, the owner of ninety-nine percent of the channel's share quotas; in effect, a self-grant that raised money laundering concerns.[25] For his part, Mesa refused to make a definitive statement on the allegations during his 2019 presidential bid, asserting that he would not respond to the "dirty war" being waged by his electoral opponents. At the same time, he affirmed that it was "based on false testimonies, on false investigations, and on the fact that, if it was an irregular act, it was carried out more than sixteen years ago".[26]

2002 general election

[edit]The MNR closed its Extraordinary National Convention on 3 February with the announcement of Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada as the party's presidential candidate, accompanied by Carlos Mesa as his non-partisan running mate. Accepting the nomination, Mesa cited resolving the economic crisis and fighting institutional corruption as the main factors in his decision to join the electoral binomial.[27] At first glance, election day on 30 June yielded an electoral victory for the Sánchez de Lozada-Mesa ticket amid a well-conducted and orderly process, generally accepted by the contending parties and their supporters. But with a plurality of just 22.5 percent, the MNR emerged as the only traditional party that could claim a modicum of popular support. Second and third place, respectively, went to the Movement for Socialism (MAS-IPSP) of the indigenous cocalero activist Evo Morales and the New Republican Force (NFR) of Cochabamba Mayor Manfred Reyes Villa; each of them took a twenty percent share of the vote. Paz Zamora's Revolutionary Left Movement (MIR) came fourth with 16.3 percent, while Nationalist Democratic Action (ADN)—the party holding the incumbent presidency—did not even reach four percent.[28] The blow to the country's traditional party system resulted in a tense runoff in which Sánchez de Lozada was forced to form an unlikely coalition with Paz Zamora in order to shore up a majority of congressional support. With eighty-four votes in their favor, Congress elected Sánchez de Lozada and Mesa as the constitutional president and vice president on 4 August, taking office two days later.[29][30]

A frustrated vice presidency

[edit]The fight against corruption

[edit]

In keeping with his campaign promise to make fighting corruption the central point of his administration, Mesa, on 11 August 2002, launched the Technical Unit against Corruption under the leadership of the journalist Lupe Cajías. The unit was set as a component of the Vice Presidency, operating independently of the Prosecutor's Office.[31] In addition to Cajías, it was composed of a "petite cabinet" consisting of José Galindo, Jorge Cortés, and Alfonso Ferrufino.[32] On 12 August 2003, the post was refounded as the Secretariat of the Fight against Corruption, which Mesa credited to be "without doubt the greatest contribution of my [vice presidential] management".[33] Two days after his assumption to the presidency, Mesa elevated the secretariat to the high executive level as the Presidential Anticorruption Delegation.[34]

Mesa's anti-corruption efforts were not without criticism. A year into her administration, Cajías admitted that her team had "barely scratched corruption" and that the post suffered "structural issues".[35] One such issue was the lack of coordination between the secretariat and other parts of the judicial system; prosecutors annulled various cases presented by her office, and the ambiguity of the office's functions eventually relegated it to issuing opinions and periodically publishing public reports on alleged acts of corruption.[36]

Mesa attributed many of the shortfalls of his anti-corruption work to a lack of cooperation from the president. One example came in July 2003 when Secretary Cajías issued Report N° 13. A contingent of conscripts and 180 soldiers of the Bolivian Army had been illegally forced to work harvesting Macororó on the Santa Monica farm in the Chiquitos Province of Santa Cruz for no wage and in conditions of general servitude.[37] The case implicated Minister of Defense Freddy Teodovich and Santa Cruz Prefect Mario Justiniano. For this reason, on 10 July, Mesa met with Sánchez de Lozada to request the dismissal of Teodovich, an action the president refused to take because the minister was an influential component of the cabinet and the MNR. Mesa considered this a revocation of the president's promise to allow him to freely take anti-corruption measures, and the incident served to aggravate festering grievances between the two.[38]

Black February

[edit]February 2003 presented the first significant ordeal that shook Mesa's confidence in the government. On the ninth, President Sánchez de Lozada, under pressure from the International Monetary Fund to significantly reduce the country's fiscal deficit, presented a new tax bill that, among other factors, imposed a salary tax on workers making a certain threshold of income. The response was near-universal outrage and a series of protests that after a few days were joined by the National Police Corps.[39][40] Given the absence of law enforcement, the demonstrations quickly devolved into riots, which eventually forced government officials to flee their offices. In his account of events, Mesa states that "what I saw was hell". At 5:00 p.m. on 12 February, Mesa, sequestered at the president's private residence, was informed that the Vice Presidency had been set aflame by vandals, an action he describes as "my apocalypse". "It seemed to me that all the illusions of public service I promised on 6 August upon taking office were shattered".[41]

Black October: Mesa pulls out

[edit]A few days ago, my country lived through serious episodes of violence, which have forced us to reflect. We are aware of the fact that the last twenty-one years of democracy — the longest uninterrupted period in our history — are at stake as we face the legitimate pressure exercised by the marginalized sectors of our society, who deserve our attention ... Loss of trust in these essential elements of democracy is one of the greatest dangers to the future of our society.

— Carlos Mesa, Address to the 58th United Nations General Assembly, 24 September 2003.[42]

By September, the simmering popular grievances of the time, mainly related to the export of natural gas to the United States through Chile, had ignited into nationwide social unrest. On 12 October, Mesa arrived in La Paz for a meeting with the president, flying in by helicopter due to the ongoing blockades making accessing the capital by land impossible.[43] At 1:34 p.m., Mesa ate lunch with Sánchez de Lozada at the presidential residence in San Jorge, where he pleaded with the president to call a referendum on gas and open up the possibility of a constituent assembly. Sánchez de Lozada, whom Mesa describes as "the most stubborn man I have ever met", remained steadfast in his refusal to give in to social demands, causing the vice president to snap at him that "the dead are going to bury you".[44] Amid their heated discussion, the government's bloody suppression of demonstrations in El Alto began to count its first deaths. Reports of the massacre of protesters, which Mesa learned from the media, definitively ruptured relations between him and Sánchez de Lozada.[45] The following day, the vice president publicly withdrew his support for the government. In his statement, Mesa outlined that the cost of human lives was something that his "conscience as a human being cannot tolerate", and he implored the government to "seek a position of dialogue and establish peace".[46] At a press conference held three days later, he ratified his refusal to cooperate, stating: "I do not have the courage to kill, nor will I have the courage to kill tomorrow. For that reason, it is impossible to think about my return to government".[47]

Between the thirteenth and the seventeenth, Mesa withdrew to his private residence. Crucially, however, he determined not to resign from the vice presidency. He later recounted that the decision came from his memory of the 2001 crisis in Argentina. During that time, President Fernando de la Rúa resigned, causing a crisis of succession because Vice President Carlos Álvarez, in protest, had vacated the office the year prior. According to Mesa: "If there was any value in the position, I thought, it was precisely guaranteeing democratic continuity in extreme cases".[48]

Mesa's decision was met with harsh criticism by sectors still loyal to Sánchez de Lozada. Among the leadership of the MNR, it was made clear that the party was "upset with Mr. Carlos Mesa", while legislators of the MIR accused him of failing to fulfill his duty as a mediator between Congress and the government.[49] According to Edgar Zegarra: "he did not tell us absolutely anything about the decisions he was going to make", a fact which the MNR deputy claimed was a sign of "deep disloyalty" on Mesa's behalf.[50]

At the same time, on 14 October, the United States Department of State informed Mesa that the US "would not under any circumstances support a possible government headed by [him]". Two days later, US Ambassador David N. Greenlee personally met with Mesa at his home to request that he return to the government, which he refused to do.[51] Given that, Greenlee recounts asking Mesa that "if you can't support the president anymore, why don't you resign?". For the ambassador, the question was a "philosophical point, not a political one", but it nonetheless fomented an untrusting relationship between the two. At the end of their discussion, it was learned that the press had intercepted Greenlee's radio traffic and had gathered outside Mesa's home. Before television crews, the two spoke of a "friendly and constructive conversation", though Greenlee states that "it wasn't of that kind".[52] The following day, with it becoming increasingly clear that Sánchez de Lozada would soon step down, the Department of State conceded and informed Mesa that the US would support his succession.[51]

At midday on 17 October, Minister of the Presidency Guillermo Justiniano called Mesa to inform him that the president would soon resign and invited him to discuss conditions surrounding his departure. Mere hours later, however, Justiniano called again to tell Mesa that Sánchez de Lozada had already left the Palacio Quemado. At 6:00 p.m., Hormando Vaca Díez and Oscar Arrien, presidents of the Senate and Chamber of Deputies, visited Mesa to inform him that they would soon accept the president's resignation and that constitutional succession corresponded to him. At the same time, they insisted that he pledge to stay in office for the mandated term ending on 6 August 2007.[51]

Presidency (2003–2005)

[edit]Without ballot boxes or rifles

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Swearing-in of President Carlos Mesa | |

Carlos Mesa delivers his inaugural address before the National Congress | |

Between 5:25 p.m. and 10:30 p.m., the presidency remained effectively vacant.[48] At a plenary session of the National Congress, an overwhelming majority of ninety-seven to thirty legislators—with the exception of all but one member of the MNR—voted to accept Sánchez de Lozada's resignation.[53][54] Vice President Mesa was subsequently sworn in as the 63rd president of Bolivia, assuming office through constitutional succession.[55][56]

Mesa opened his inaugural address with a conciliatory tone, emphasizing that "Bolivia is not yet a country among equals".[57] He outlined his intent to call for a binding referendum on gas exports, promised to review the privatization of hydrocarbons, and pledged to call for a constituent assembly to revise the Constitution in hopes of addressing ethnic and regional divisions.[58] These points became known as the "October Agenda" and composed the core of Mesa's government program during his presidency.[59] His accession to office was largely well received by the country's social sectors, who heeded his request for demobilization and an end to the blockades.[57] From Cochabamba, Evo Morales indicated that the ouster of Sánchez de Lozada was "just a small victory" but also expressed his willingness to support Mesa's policy initiatives.[60][61]

Mesa's investiture was met with far more skepticism among the traditional parties. His pledge to form a non-partisan cabinet devoid of participation from any political party adherents, which Mesa phrased as a "sacrifice" they would have to make, was a significant blow to their influence, described by one MNR deputy as "political suicide".[57] The second shock came when Mesa announced his intent to bring his term to a conclusion before 2007, as legally prescribed. He called for a "transitional" government and left Congress responsible for setting a date for new elections.[60] In January 2004, amid a high approval rating and broad popular support, Mesa retracted this promise and announced his intent to complete Sánchez de Lozada's term.[62]

Entering the Palacio Quemado, Mesa was met with an executive headquarters entirely devoid of personnel, save for the presence of his family and some friends who came to visit. There, he spoke with Bishop Jesús Juárez, who suggested to him that to guarantee the country's pacification, he had to be in El Alto the next day.[63] Mesa heeded the advice, traveling in his first full day as president to the former epicenter of the social conflicts to participate in a ceremony in tribute to the victims of the previous government's violent occupation of the city. Before a crowd of some 8,000 people, he declared that his government would grant compensation of Bs50,000 to the relatives of the deceased and, most importantly, announced an inquiry into those culpable for the previous week's repressions.[64] With the slogan "neither forget, nor revenge: justice!", Mesa promised that he would ask Congress to begin a "responsible investigation" that would establish the responsibility of Sánchez de Lozada and members of his government for the numerous deaths caused during the October crisis.[65] Almost a year later, on 14 October 2004, the National Congress, by a vote of 126 to thirteen, authorized a trial of responsibilities against Sánchez de Lozada and his entire cabinet under the purview of the Law of Responsibilities (Law N° 2445), precisely promulgated by the ex-president. Mesa applauded its passage as a "historic decision" that "strengthens democracy and renews civic faith in its institutions".[66][67]

Domestic policy

[edit]Economy

[edit]

Among the most pressing challenges facing the early Mesa government was the ongoing economic recession—at the start of 2003, the fiscal deficit lay at 8.7 percent of GDP.[68] On 1 February 2004, Mesa laid out his economic program aimed at reducing government waste through fiscal austerity and the imposition of new taxes on the nation's highest earners. Within the public service sector, he implemented a ten percent reduction in his own salary as president and a five percent cut in the wages of all high officials, as well as eliminated the "bonuses" of up to US$4,000 granted to ministers, vice ministers, and legislators through which their wages had nearly doubled. On that point, Mesa introduced measures that prohibited government officials from having wages higher than the president's. In the private sector, he imposed a tax on bank transactions and 1.5 percent of the net worth of those making more than US$50,000.[69][70] At the conclusion of Mesa's first full year in office, the fiscal deficit had been reduced to 5.5 percent and was at 2.4 percent by the end of 2005.[71][72]

Judiciary

[edit]Since 1999, the Supreme Court of Justice had been operating at a reduced capacity. Congress had left several vacancies due to its inability to nominate judges who could gain the support of two-thirds of the legislators, causing delays in the judicial system because the Court could not reach the majorities necessary to adopt rulings. In light of the parliamentary recess, on 31 July 2004, through Supreme Decree N° 27650, Mesa swore in six new acting Supreme Court magistrates, two judicial counselors, and nine district prosecutors.[73] Mesa justified that in this way, he had "guarantee[d] the independence of the judicial power, starkly controlled by the parties ...". The recess appointments were challenged by Congress, which filed a motion with the Constitutional Court on the grounds that Mesa had violated the separation of powers. On 11 November, the Court ruled against Mesa and annulled the appointments.[74][75]

Constitutional reform

[edit]The primary barrier to Mesa's October Agenda, particularly regarding the promise of a referendum and a constituent assembly, was that the Political Constitution of the State did not prescribe any mechanisms to carry out either venture. For this reason, the first step toward the president's program was to amend said Constitution. To do this, Law N° 2410 On The Necessity of Reform to the Constitution—promulgated in 2002 by then-president Jorge Quiroga—was unarchived in order to provide a legal framework for the new alterations.[76][77] On 20 February 2004, Congress sanctioned, and Mesa promulgated Law N° 2631, amending the Constitution to allow for a constituent assembly and the ability to call for either a citizen legislative initiative or a referendum. In addition to the main points, the opportunity was also taken to abolish parliamentary immunity and allow for dual citizenship.[78][79]

Hydrocarbons and gas

[edit]2004 gas referendum

[edit]

| ||

| Results | ||

|---|---|---|

| Source: Nohlen[80] | ||

A few months after the formalization of the new legal structure, on 13 April 2004, Mesa issued the call for a referendum on gas, opting to do so through supreme decree given a National Congress whose majority opposed his agenda.[81][82] The latter decision was the basis for the traditional parties' objection to the plebiscite; the MIR, ADN, and sectors of the MNR, among other criticisms, voiced their opinion that the convocation of the referendum through any form other than a law passed by the legislature was illegal. Legislators of Solidarity Civic Unity (UCS) filed two lawsuits with the Constitutional Court alleging the unconstitutionality of the referendum. Days before the vote, the Court ruled in favor of Mesa and the National Electoral Court.[83]

Simultaneously, the five questions, drafted by both Mesa and MAS representatives,[e] caused a divide in the labor and social movements because they did not directly address the nationalization of gas reserves, an action supported by over eighty percent of the country. The country's largest workers' unions—the Bolivian Workers' Center (COB), the Regional Workers' Center of El Alto (COR-El Alto), the Unified Syndical Confederation of Rural Workers (CSUTCB), and the Gas Coordinator, among others—all voiced their discontent with this crucial omission and called for a boycott of the vote, promoting roadblocks and demonstrations to block access to polling sites.[84][85][86] On the other hand, the Bartolina Sisa Confederation, as well as peasant unions in Potosí, Oruro, and Cochabamba backed the vote in support of Morales.[87] For his part, Morales encouraged a "yes" vote on the first three questions and a "no" on the last two, which concerned issues surrounding exports. Mesa's campaign denounced the boycott and ramped up security at polling centers to defend against threats of violence, while the Electoral Court imposed a fine of Bs150 (US$19) for those who did not vote.[88]

The outcome of the 18 July vote yielded largely positive results for the Mesa administration. Labor protests failed to significantly reduce turnout, which came in at 60.06 percent, a figure that, while the lowest of any election since the transition to democracy in 1982, was still substantial. The Electoral Court argued that, as a referendum, participation levels were not comparable to previously held general or municipal elections. Most importantly, all five questions passed by broad margins. Questions one through three regarding the repeal of Sánchez de Lozada's hydrocarbons law, State recovery of hydrocarbon ownership at the wellhead, and the reestablishment of YPFB all passed with over eighty percent of the vote—question two achieved over ninety percent. Meanwhile, coinciding with the position of the MAS, questions four and five on exports saw the least support, though they still received over fifty percent and sixty percent of the vote, respectively.[89] Mesa hailed the results as a significant victory and a vote of confidence in his administration, later calling it "the brightest moment of our government".[81][90][91]

2005 Hydrocarbons Law

[edit]Immediately following the referendum, Mesa began negotiating with Congress, whose participation was necessary to formulate and eventually sanction a law on hydrocarbons. His first step was to introduce the Law of Execution and Compliance of the Referendum—dubbed the "short law"—to establish a clear interpretation of the vote's results and commit to comply with them. Mesa was adamant that the short law must be "physically separate" from any eventual hydrocarbons legislation. Regardless, the measure was roundly rejected by the legislature, which insisted on a singular hydrocarbons bill. As a result, Mesa announced on 20 August that he would not enact any legislation authorized by Congress until an agreement was reached, a pledge he was forced to retract two days later amid criticism that he was jeopardizing the convocation of municipal elections.[92] After a few weeks of negotiations, the president relented and agreed to present a solitary "large law" to Congress for consideration.[93]

Ultimately, without a party base of his own, Mesa was incapable of overcoming Congress's ability to block his policy initiatives. In late October, peasant and mining sectors led by Morales and the COB conducted mass demonstrations in La Paz, blockading the streets in and around Congress. On 20 October, faced with immense external pressure from over 15,000 peasant protesters arriving from Caracollo, Congress discarded the president's bill and agreed to move forward with the one proposed by the Mixed Commission for Economic Development, headed by Santos Ramírez of the MAS.[94] With victory at hand, Morales agreed to demobilize his followers.[95] After the demise of Mesa's project, negotiations moved forward over the more radical proposal. The primary point of contention between parliamentarians of different parties surrounded question two of the referendum and what exactly "recover[y of] ownership over all hydrocarbons" meant. While more radical sectors called for complete nationalization of the industry, the MAS took a more moderate stance, demanding that oil companies be subject to a royalty of fifty percent of their profits. The compromise of the traditional parties was to approve a draft on 3 March 2005 that kept the preexisting eighteen percent royalty in place but added a thirty-two percent profits tax that, cumulatively, would reach fifty percent.[96] In response, MAS sectors mobilized their bases in Cochabamba and Chuquisaca, initiating blockades and roadblocks, actions that shattered the tacit alliance Morales had shared with Mesa up to that point.[97]

The dramatic upturn in the social climate placed Mesa in a precarious political position—one that urgently necessitated a skillful maneuver in order to circumvent a repeat of the government repressions of October 2003, which Mesa refused to allow. The scheme ultimately devised was two-fold: the presentation of the president's revocable resignation to Congress and a simultaneous televised address to the nation.[97] In a forty-five-minute speech broadcast on radio and television, Mesa put to use his oratory skills, denouncing both left-wing labor sectors as well as conservative autonomists and business elites and directly calling out Evo Morales by name. In addition, he reiterated his statement that "I am not willing to kill" and promised that "there will be no deaths on my back" before announcing to the nation his intent to resign from the presidency on the grounds that it was impossible to govern under the threat of blockades.[99] The gamble succeeded in inverting middle-class sentiment in his favor and against his opponents. Soon after the speech, a mass demonstration reaching approximately 5,000 people assembled outside the Plaza Murillo to support of the continuity of Mesa's mandate. Similar gatherings took place in other cities.[100][101]

With popular support and political momentum at his back, Mesa immediately set about exerting pressure on Congress. Within hours, at a plenary session of legislators convened to formulate a response to Mesa's resignation, Minister of the Presidency José Galindo laid out the president's terms for remaining in office. After three days of negotiations, Congress unanimously voted to reject Mesa's resignation on 8 March. In exchange, the legislature committed to a four-point agenda: expedite the drafting of the hydrocarbons bill; begin the process of approving an autonomy referendum, the democratic election of prefects, and the convocation of a constituent assembly; construct a national "social pact"; and initiate efforts to end the ongoing blockades. The agreement was formalized between Mesa and six of the eight congressional parties: the traditional right-wing parties, embattled and under pressure, accepted, while the MAS and the Pachakuti Indigenous Movement (MIP; a related left-wing party) refused to sign, and from that point were marginalized entirely, solidifying the split between Mesa and Morales for the rest of his administration.[102][103]

Mesa's brief alliance with the conservative sectors of Congress proved tenuous. Recalling the accord, Mesa regretted that "I wasted the chance; I accepted a bad agreement with Congress, a generic document, of moral commitments that were never fulfilled". He further outlined that a better course of action would have been to impose his own hydrocarbons bill as a condition for withdrawing his resignation.[105] On 15 March, the Chamber of Deputies approved the Hydrocarbons Law, maintaining the eighteen percent royalty and thirty-two percent tax. Despite not meeting the opposition's demands, Morales relented and called off the ongoing strikes. Mesa, however, maintained that the country did not have the economic capacity to carry out the law and argued that the new tax should be implemented gradually, starting at twelve percent and increasing to thirty-two percent within a decade.[106]

Nonetheless, on 6 May, Congress moved forward and passed the controversial bill. Despite having drafted it themselves, the failure to agree on the fifty percent royalty led the MAS to near-unanimously vote against it.[107] Faced with two unappealing choices of either promulgating the law or vetoing it, Mesa took a third option: neither. As stipulated by Article 78 of the Constitution: "Laws not vetoed or not promulgated by the president of the republic within ten days from their receipt, will be promulgated by the president of the congress". On 16 May, President of the Senate Hormando Vaca Díez signed the bill into law and criticized Mesa for "[bringing] the country to a point of crisis and uncertainty".[108][109]

Autonomies

[edit]One of the major challenges to the Mesa government was the increasing calls for decentralization from business and civic sectors in the Santa Cruz Department. For years, the national government had systemically blocked the issue of departmental autonomy and the democratic election of prefects. The Banzer and Quiroga administrations sidestepped it entirely, while Sánchez de Lozada was actively hostile to the prospect, viewing it as the basis for the collapse of the unitary state.[110] Mesa took a different stance on the issue, announcing on 20 April 2004 his support for regional autonomy. He outlined his government's intent to address the matter through the convocation of a constituent assembly that would amend the relevant articles in the Constitution in order to provide for the decentralization of the country and the election of prefects and departmental councilors by popular vote. In tandem, he issued two decrees that month: one served to strengthen departmental councils while the other determined the administrative decentralization of regional health and education services.[111][112][113] The response from Santa Cruz civic leaders, however, was unsupportive of Mesa's proposal. On 22 June, under the leadership of Rubén Costas—head of the Pro Santa Cruz Committee—a civic council was convened that approved an eleven-point document known as the "June Agenda" against blockades, centralism, and violence. It demanded a national referendum on autonomies and began collecting signatures for a departmental plebiscite to be held prior to the convocation of the constituent assembly.[114]

This context precipitated an antagonistic relationship between the Mesa administration and Santa Cruz civic leaders and business elites for the duration of his mandate. Although Mesa's policy proposals remained in favor of a move toward autonomy, his approval rating in the department fell from sixty-one percent in June to thirty-six percent by the end of 2004.[115] The culmination of this animosity came on 30 December when the government announced the termination of its fuel subsidy in order to reduce the rate of smuggling. The result was a twenty-three percent increase in the price of diesel and a ten percent gasoline hike.[116] The unpopular measure—dubbed the "dieselazo"—generated nationwide protests from both left-wing indigenous and labor groups and right-wing business sectors.[117] Most seriously, autonomist groups in Santa Cruz, joined later by civic groups in Tarija, quickly coopted the demonstrations in those departments, adding the call for autonomy to their list of demands even after the government agreed to reduce the diesel increase to fifteen percent.[118][119] On 21 January, the Armed Forces signaled to the president their willingness to intervene in the event that Santa Cruz moved to declare itself autonomous in violation of the Constitution. Faced with the possibility of an armed confrontation similar to that of October 2003, Mesa, on 26 January, resolved with his cabinet to allow the Cruceños to move forward with self-rule unimpeded. The following day, with news that the Santa Cruz Youth Union had decided to seize all public institutions in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Mesa gave the order to withdraw all civil and police personnel from public buildings, including the prefecture, in order to avoid armed conflict.[120] On 28 January, Santa Cruz was proclaimed an autonomous department at a cabildo held at the foot of the Christ the Redeemer Monument. The declaration came with the formation of a provisional assembly that would negotiate with the government for a departmental autonomy referendum in order to legitimize the new authority, which at the moment contravened the Constitution.[121][122] That same day, Mesa issued Supreme Decree N° 27988, which called for the election of prefects in all nine departments. Since the Constitution granted the power to designate prefects solely to the president, the decree worked around that by constraining the head of state only to appoint those who obtained a majority of the popular vote.[123][124] The decree was formalized by a complementary law passed by Congress on 8 April.[125] On 11 February, Mesa delegated to Congress the task of setting a date for the autonomies referendum.[126]

Foreign policy

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Signing of the gas export contract to Argentina | |

Mesa meets with Argentine President Néstor Kirchner, 22 July 2004. | |

Argentina

[edit]On 15 April 2004, Mesa authorized an agreement with Argentine President Néstor Kirchner allowing for the sale of four million cubic meters daily of Bolivian gas for a six-month period with the possibility of renewal depending on the outcome of the July referendum.[127] The arrangement was supported by civic groups in Tarija—home to eighty-five percent of the country's natural gas—but was met with suspicion by certain labor sectors who viewed it as a possible roundabout way for Bolivian gas to be exported to Chile through Argentina.[128] In view of this, the Mesa administration conditioned the sale on the promise that not "one molecule" of Bolivian gas could be exported to Chile. Doing so would constitute a contract violation on the part of Argentina.[129] Mesa met with Kirchner twice more during his presidency, this time in Bolivia, once for a short discussion in July and another in October 2004.[130] In the latter, the two presidents signed an agreement that increased Bolivian gas export volumes from 6.5 million to 26.5 million cubic meters per day to help mitigate the Argentine energy crisis.[131]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Monterrey Special Summit of the Americas | |

Mesa with U.S. President George W. Bush in Monterrey, Mexico, 13 January 2004. | |

Chile and the Maritime Demand

[edit]As with near-universally all previous governments, the relationship between Bolivia and Chile during the Mesa administration centered fundamentally on Bolivia's claim of sovereign access to the Pacific Ocean, a dispute which, by 2004, had reached its centennial without compromise. Just under a month into Mesa's presidency, the first discussions surrounding the maritime issue took place. On 14 November 2003, during the ongoing Ibero-American Summit, Mesa met privately with Chilean President Ricardo Lagos at the Los Tajibos Hotel in Santa Cruz de la Sierra. The dialogue between the two heads of state concluded with an agreement in principle on a sovereign corridor connecting Bolivia to the Pacific through a 10 km (6.21 mi) strip of land along the Chile–Peru border. As per the Treaty of Ancón, any cession of land formerly belonging to Peru necessitates Peruvian approval and, therefore, Lagos stipulated that "if there is a Peruvian yes, there will be a Chilean yes".[132]

Mesa raised the maritime claim again at the Monterrey Special Summit of the Americas in January 2004. There, he emphasized the good relationship between the two countries but expressed his view that such relations required the resolution of issues that "for a reason of justice" must be resolved.[133] Mesa's statements opened a rift between himself and Lagos, who expressed his "regret [for] what happened in Monterrey because these are spaces to advance on collective and multilateral issues".[134] Nonetheless, Mesa was received with praise by the National Congress, which declared "its strongest and most determined support" for the president. Later that month, at a seven-hour session of parliament, Congress declared the maritime claim to be an "inalienable right of the Bolivian people" and issued its approval for Mesa's strategy of multilateralizing the demand in order to gain support from as many nations as possible.[135][136]

At the 34th General Assembly of the Organization of American States held in Quito, Ecuador, the Bolivian delegation distributed its Libro Azul, which recounted the government's interpretation of events surrounding the War of the Pacific and justifies the country's historical claim. The 35th OAS General Assembly was held in Fort Lauderdale from 5 to 7 June 2005; Mesa issued his definitive resignation on 6 June. It was the last time the outgoing government addressed the maritime claim, bringing an end to Mesa's strategy against Chile.[137]

Peru

[edit]

At a meeting in Lima held on 4 November 2003, Mesa and Peruvian President Alejandro Toledo agreed on the framework for a common market between the two states in order to support greater cultural, commercial, and economic integration as advocated by the Andean Community.[138] Days after voters approved gas exportation as part of national policy in the gas referendum, the Bolivian government scheduled talks with their counterparts in Peru to discuss the topic.[139] On 4 August 2004, Mesa and Toledo signed a letter of intent promising to analyze the joint exportation of natural gas. The deal granted Bolivia a special economic zone centered on the southern port of Ilo, from where it could export its gas to lucrative markets in Mexico and the United States. The agreement allowed Bolivia access to the Pacific for the first time in over a century.[140] Days later, the two presidents, along with Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, inaugurated two bridges connecting Bolivia and Peru to Brazil. Through this, Toledo expressed his hope that a tripartite market between the three countries could pave the way for broader continental integration.[141]

Definitive resignation

[edit]Despite enjoying an approval rating of over sixty percent, Mesa's inability to find a compromise with the National Congress, especially after his break in relations with the MAS, led him to call for an early end to his term. On 15 March 2005, less than a week after Congress rejected his resignation, Mesa announced his intent to introduce a bill that would advance the call for general elections to 28 August, cutting short his term by two years.[142] Two days later, Congress rejected his proposal under the justification that it "lack[ed] a legal basis".[143]

After returning the unenacted hydrocarbons bill to Congress, Mesa attempted to salvage his domestic policy agenda by calling a "National Meeting for Unity" to be held in Sucre on 16 May. The conference would have sought to find consensus on the hydrocarbons law and establish concrete dates for the convocation of an autonomies referendum and elections for a constituent assembly and prefects. Ninety-seven sectors were invited, including the three branches of government, ex-presidents, heads of political parties, mayors of the nine departmental capitols and El Alto, the association of municipalities, the presidents of the nine departmental civic committees, four representatives of indigenous organizations, two from trade unions, and two from large businesses.[144][145] While the Catholic Church, the Human Rights Assembly, and some civic groups agreed to participate, most political parties rejected the meeting, including both the MNR and MAS. Mesa was ultimately forced to suspend the event after Congress declined to attend.[146][147]

By this point, the country faced increasingly debilitating strikes and demonstrations from opposing groups seeking conflicting goals. The MAS demanded the urgent convocation of a constituent assembly to rewrite the Constitution. They were supported by trade unions, which additionally called for the immediate nationalization of gas. In the eastern departments, protests were held calling for a referendum on autonomies. The unrest was exacerbated by the indecision of Congress, which remained deadlocked over whether to convene the constituent assembly and later hold the autonomies referendum or hold both constituent elections and the referendum simultaneously. Finally, on 2 June, Mesa opted to circumvent the legislature and, by supreme decree, scheduled the referendum and elections for the constituent assembly for 16 October.[148][149]

Mesa's actions failed to quell the unrest and were rejected by both left-wing and right-wing sectors of the country. Faced with the tense political situation and unwilling to allow military action against protesters, Mesa tendered his resignation on 6 June. With that, the responsibility fell to Congress to accept it and swear in a new individual to the presidency. The candidate next in line to succeed Mesa was Hormando Vaca Díez, the president of the Senate, followed by Mario Cossío of the Chamber of Deputies.[150] Viewing that the country would not accept such a succession by members of the traditional political parties, Mesa called on Vaca Díez and Cossío to renounce their succession rights to avoid an "explosion" in the country. This request was not considered by Vaca Díez, who announced his intention to convene a session of Congress in Sucre—La Paz was almost entirely blockaded—to accept Mesa's resignation and install himself as president.[151] After three days of resistance, Vaca Díez conceded to popular pressure and, along with Cossío, the two legislative heads renounced their right to succession.[152] At 11:45 p.m. on 9 June 2005, Eduardo Rodríguez Veltzé, the president of the Supreme Court of Justice, was sworn in as the 64th president of Bolivia at an extraordinary session of Congress held in Sucre.[153] The following day, Mesa received Rodríguez Veltzé in La Paz. For Mesa, "that moment had an immense symbolic load. I had entered through the front door and was leaving through the front door, with my forehead high and looking the country in the eye".[154]

Post-presidency (2005–2018)

[edit]

After his departure from the Palacio Quemado, Mesa retired from politics and returned to his work as a journalist. In 2008, he published Presidencia Sitiada, a memoir of his time as head of state. The following year, together with Mario Espinoza, he directed, wrote, and narrated Bolivia Siglo XX, a documentary series covering the most important events in twentieth-century Bolivian history.[104] On 7 December 2012, the Association of Journalists of La Paz awarded Mesa the National Journalism Award for his extensive contributions to Bolivian media.[155][156]

Spokesman for the Maritime Demand

[edit]On 28 April 2014, now-president Evo Morales announced the appointment of Mesa as a member of the team of the Strategic Directorate of the Maritime Claim (DIREMAR). As outlined by the president, Mesa's task would be to represent Bolivia's maritime claim in all international forums, presenting the legal and historical bases of the country's claim against Chile, for which it had filed a lawsuit with the International Court of Justice.[157][158] The decision to appoint Mesa did not come as a surprise; several politicians in past weeks, including President of the Chamber of Deputies Marcelo Elío Chávez, had suggested his inclusion on the DIREMAR team due to his historical expertise. Speculation had even arisen that he might be appointed ambassador to Peru, an extreme Morales was not entirely comfortable with and which he circumvented by specifying that Mesa's new post would not constitute an official diplomatic office because "it is not necessary for him to have this position [since] as a former president and former vice president he has all the authority to assume this responsibility".[159] This fact was reiterated by Mesa, who stated that he had agreed with the president that "I am not a public official, I will not be appointed, nor will there be a swearing-in ceremony". He further noted that he would hold his position ad honorem and would not receive a salary for his work.[160] However, as noted by economist Alberto Bonadona, following his appointment, the government began paying Mesa the life annuity that corresponded to him as a former president, which it had previously blocked from being delivered. "With all certainty, they [paid] him retroactively", Bonadona stated.[161]

Mesa began his task with an eye towards the 50th G77 + China Summit, hosted by Bolivia in Santa Cruz de la Sierra between 14 and 15 June of that year. While Mesa stated that Bolivia would not seek an official statement of solidarity from the member states present, he highlighted the gathering as an opportunity to disseminate the country's maritime claim and stated that the meeting "should have the issue of the sea as a fundamental aspect".[162][163] On 16 June, Mesa and Morales jointly presented El Libro del Mar at a ceremony in the Palacio Quemado. The book, distributed to the attendees of the G77 in the previous days, described the essential arguments that Bolivia intended to present to the international community.[164][165]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Interview in Santiago, Chile | |

Juan Manuel Astorga interviews Mesa for the program El Informante | |

During this time, a notable dichotomy between Mesa's international and domestic relationship with Morales developed. On the one hand, he supported and closely cooperated with the president on matters relating to the maritime lawsuit. At the same time, he remained harshly critical of the government's undemocratic tendencies, and the ruling party filed various legal complaints against him, the most notable being the Quiborax case in which he was accused of breach of duties for actions taken during his presidency.[166][104] Vice President Álvaro García Linera described Mesa as "an excellent explainer of the maritime cause" but stated that "as a politician, internally, he is a resounding failure".[167] Nonetheless, in 2019, Mesa affirmed that, if asked to return as spokesman for the maritime cause, he "would do it again one, two, five, 100, 200 times more".[168]

In late September 2018, Mesa traveled to The Hague to hear the ICJ's final ruling.[169] In an interview for the Chilean newspaper La Tercera, Mesa assured that "the Bolivian people are prepared to receive the ruling regardless of its content" and urged both countries to abide by the court's decision.[170] On 1 October 2018, by a vote of twelve to three, the ICJ ruled that Chile was not obligated to negotiate sovereign access to the Pacific with Bolivia.[171] Shortly after, Mesa called on Bolivians to "accept the ruling even though it seems unfair". He urged the government to respect the decision and asked that it move forward with a new policy towards Chile with the understanding that it is not obliged to negotiate.[172]

Return to politics (2018–present)

[edit]In mid-2018, Mesa appeared as a lead contender against Morales in early voting intention polls. On 29 July 2018, the company Mercados y Samples released a poll for Página Siete that showed Mesa with a first-round favorability of twenty-five percent, two points behind Morales' twenty-seven percent. Such a result would launch a runoff in which polling gave Mesa an over ten-point victory of forty-eight percent over Morales' thirty-two percent. MAS Senator Ciro Zabala credited this polling victory to the opposition making Mesa seem "victimized" by the Quiborax case. This point was reiterated by Deputy Edgar Montaño, who admitted that the controversy "makes Mesa grow". On the other hand, opposition leaders affirmed that Mesa's popularity was due to what they claimed to be political persecution by the government against him.[173]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| For a Government of Citizens | |

Carlos Mesa announces his candidacy for the presidency | |

In an interview with Erbol on 19 September, Mesa declared that he would not make any political statements or comment on his potential candidacy "as long as the issue of the sea is the fundamental question", committing himself entirely to his duties until the ruling by The Hague on 1 October.[174] On 5 October, the Revolutionary Left Front (FRI) formally invited Mesa to be the party's presidential candidate in the 2019 elections. While Mesa claimed that he would make a decision "in the next few hours", both Walter Villagra, secretary-general of the FRI, and Mesa's lawyer, Carlos Alarcón, confirmed that he had already accepted.[175] The following day, Mesa formally launched his 2019 presidential candidacy. In a video message titled "For a Government of Citizens", Mesa stated that "I have made ... the decision to be a candidate for the presidency of the State. And I do so for a very clear reason, because this is a time of historical inflection, because we are at the beginning, on the threshold of a new time".[176] He further outlined his intention to form "a citizen movement" which would break "the exhausted cycle" of over a decade of MAS rule.[177] Mesa's announcement was hailed by various opposition groups, including leaders both the National Unity Front (UN) and the Social Democratic Movement (MDS), who signaled their hopes of sealing an alliance with the FRI.[178]

Leader of Civic Community

[edit]On 24 October, La Paz Mayor Luis Revilla announced that his Sovereignty and Liberty (SOL.bo) civic group had decided to support Mesa's candidacy.[179] After a 26-minute tour through the Central Urban Park of La Paz on 30 October, Mesa and Revilla announced to the media that they had agreed to form a coalition between the two parties.[180] The agreement was formalized the following day[181] and registered with the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) on 13 November 2018 under the name Civic Community (CC). The alliance initially included the FRI, SOL.bo, and over 50 citizens platforms.[182] However, CC failed to gather a fully unified opposition pact as UN and MDS formalized their own alliance while other parties registered individually.[183] Jhonny Fernández, leader of UCS, explained that sealing a deal was difficult because the FRI was "not interested in working with leaders who were in political and administrative positions in previous governments".[184]

2019 presidential election

[edit]

One of the agreements made by Revilla and Mesa was that the latter would be free to nominate his running mate.[185] On 27 November, Mesa announced that Gustavo Pedraza, his former minister of sustainable development, would accompany him as his vice-presidential candidate.[186] Civic Community opened its electoral campaign in Tarija with a "door to door" canvassing drive and the announcement of a national tour through the country.[187][188] One of Mesa's main campaign tactics was to denounce Morales' bid for a fourth term as illegal due to the fact that voters rejected abolishing term limits in 2016.[189] In that vein, he promoted the strengthening of democratic institutions and additionally ran on environmental protection and addressing corruption.[190]

Crisis: Mesa calls fraud

[edit]General elections were held on 20 October. By the following day, with a provisional count of eighty-three percent of ballots, Morales and Mesa appeared poised for a second round in December. Mesa hailed his movement's "unquestionable triumph"[f] and swiftly took steps to gather the endorsements of the other opposition parties for the "definitive triumph" in the runoff.[193] Shortly after, however, he expressed concern that the government's official live count had paralyzed at 27.14 percent and called for civic mobilizations and opposition demonstrations before the TSE and its departmental branches to avoid suspected fraud.[194] After a full day without live results, the TSE released its updated count, which placed Morales at 46.86 percent and Mesa at 36.72 percent, with ninety-five percent of votes tallied. Such an outcome gave the president an over ten-point lead by a margin of just 0.1 percent, sufficient to circumvent a runoff.[g] Mesa denounced the unexpected result as "distorted and rigged" and alleged "a gigantic fraud underway". As a result, he called for his supporters to "permanently mobilize" until a second round was agreed to.[196][197] On 3 November, in the midst of an increasingly unsustainable political situation, Mesa insisted on the resignation of the members of the TSE and the convocation of fresh general elections under the supervision of new electoral authorities, rejecting a second round as untenable while at the same time implicitly refusing to support the more radical demands from Santa Cruz civic leaders like Luis Fernando Camacho that Morales resign.[198] By 10 November, however, Mesa had joined the call for Morales to step aside "if he has an iota of patriotism left".[199] The day before that, he rejected Morales' call for dialogue with the opposition, stating: "I have nothing to negotiate".[200]

After twenty days of continuous demonstrations and with his grip on the country slipping, Morales, together with his vice president, announced his abdication on 10 November.[201] After a series of ensuing resignations that exhausted the presidential line of succession followed by two days of uncertainty, opposition senator Jeanine Áñez was proclaimed, first, president of the Senate and, through that, president of the State. Two days later, Mesa gave his support to the transitional government but assured that his alliance would not participate in it in order to focus its attention on soon-to-be called elections.[202] On 8 June 2021, Áñez testified before the Prosecutor's Office that Mesa had blocked the assumption of a MAS legislator to the presidency during the 2019 crisis. During extra-legislative meetings held to discuss a solution to the serious issues facing the country, then-president of the Senate Adriana Salvatierra, anticipating the possible resignation of Morales, raised her claim to constitutional succession and asked if the opposition would accept it. According to Áñez: "Mr. [Antonio] Quiroga calls Mr. Carlos Mesa by phone to consult him, and he replies that the public would not accept that succession [because] the protests would continue". Salvatierra announced her resignation an hour after Morales issued his.[203][204] Mesa did not comment on Áñez's testimony but in October affirmed that, at meetings sponsored by the Catholic Church and European Union, Salvatierra never raised her right to take office. He also called back to January 2020 when she reported to Los Tiempos that her resignation had been part of a political agreement made with Morales.[205]

2020 presidential election

[edit]A month after the establishment of the transitional government, Mesa confirmed that he would stand as a candidate in the rerun general elections.[206] Despite initial hopes of leading a unified front against the MAS, Mesa's campaign quickly came up against multiple presidential hopefuls, including the candidacy of President Áñez herself, which he considered a "great mistake".[207] On 3 February, a total of seven opposition fronts were registered for the new elections, including Mesa's Civic Community as well as Áñez's Juntos alliance, Luis Fernando Camacho's Creemos, and Libre21 of Jorge Quiroga, among other minor parties.[208] The fracturing of the opposition risked the dispersion of the vote and, though the various parties consolidated with the withdrawal of Áñez and Quiroga in the final weeks and days of the election cycle, Mesa's campaign was hampered nonetheless.[209][210]

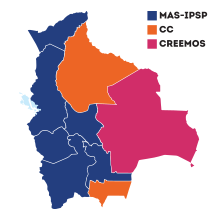

In the elections of 18 October, these factors contributed to the victory of the MAS and its candidate Luis Arce in the first round. Mesa came in second with 28.83 percent, having lost a significant percentage of the vote to Camacho, who came in third with fourteen percent.[211] Mesa conceded defeat the day after the election and noted his coalition's position as the head of the opposition in the Legislative Assembly.[212] Analysts have attributed Mesa's electoral defeat to the "passive" nature of his campaign. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Mesa's campaign remained largely virtual and failed to reach out to social sectors. At the same time, external factors such as the unpopularity of the interim government and the candidacy of Camacho, which siphoned support from Santa Cruz, contributed to Mesa's loss.[213]

Ideology and personality

[edit]Political positions

[edit]Texas A&M political analyst Diego von Vacano stated that, since his reentry into politics, Mesa has "moved to the left", largely due to the fact that "Morales shifted the entire spectrum of Bolivian politics to the left". In 2020, Mesa was the only presidential candidate who expressed a willingness to open a national discussion on issues such as gay marriage, abortion, and marijuana legalization.[214] Michael Shifter, president of the Inter-American Dialogue—of which Mesa is a member—describes Mesa as a "centrist committed to democratic values, who understands the importance of reconciliation as a condition for moving forward".[215] Personally, Mesa states that in previous years he would have considered himself a social democrat but that he no longer subscribes to any singular ideological viewpoint. At the same time, he asserts that he is not "at all from the right and of the 70s Marxist leftism, less so".[189] In an interview with El País of Tarija, Mesa affirmed that "I don't think it matters if I'm from the left, center, or right".[216]

Mesa credits his schooling at a Jesuit institution as having "always been very strong in my vision of the spiritual" but states that he has been "skeptical about religious issues for several years, the more I have delved into the subject more deeply".[217] In late 2018, he proposed the enactment of a law that would guarantee the separation of church and state as prescribed by the 2009 Constitution.[218]

In international relations, Mesa has opened up the possibility of good relations with any nation regardless of political ideology so long as they are in the "best benefit for Bolivia" and within the framework of "respect [for] democracy and human rights". He has advocated for the resumption of bilateral relations with the United States and the expansion of economic agreements with China and Russia.[219][220] When Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, Mesa decried the act as "imperialist" and called on the government to release an official condemnation.[221]

Mesa has advocated for judicial reform within the country and blamed the MAS for perverting justice to the point that it has "become a danger to human rights". In particular, he pointed to the multitude of political prisoners held by the government and the harsh prosecution of infractions committed by opposition politicians compared to those of the ruling party.[222] After the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts for Bolivia concluded a lack of judicial independence, Mesa proposed a ninety-day judicial reform plan entailing amendments to the Constitution and the organic law of the Prosecutor's Office and modifications to the system of electing magistrates and appointing national and departmental prosecutors.[223] In February 2022, CC proposed a judicial reform bill that would amend nine articles of the Constitution to guarantee judicial independence.[224]

On environmental issues, Mesa pledged to better guarantee the protection of the country's rainforests against external issues such as the fires that affected it in 2019. He also opposes the expansion of agricultural land into protected areas but has promised to seek solutions that harmonize progress and development with environmental protection.[225] In 2019 and 2020, the non-profit organization Sachamama, in partnership with leading environmental groups like the WWF, placed Mesa on its list of "The 100 Latinos Most Committed to Climate Action".[226][227] Together with Juan Carlos Enríquez, Ramiro Molina Barrios, and Marcos Loayza, he produced Planeta Bolivia, a series of five documentaries covering crucial environmental challenges facing the country in the twenty-first century. In 2017, it was screened at the 13th Inkafest, Peru's mountain film festival in Arequipa.[228]

Personality