PAVE PAWS

| PAVE Phased Array Warning System | |

|---|---|

| Massachusetts, California, Florida and Texas in United States | |

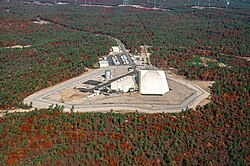

The Cape Cod Space Force Station AN/FPS-115 (white structure with circular array) on 1 October 1986 was 1 of 2 while two more FPS-115s were being built. At the beginning of the Cold War, the Cape Cod landform had a Permanent System radar station (1951 North Truro AFS), and the offshore Texas Tower 2 was at George's Bank (closed 1963). | |

| Type | Radar station |

PAVE PAWS (PAVE Phased Array Warning System) is a complex Cold War early warning radar and computer system developed in 1980 to "detect and characterize a sea-launched ballistic missile attack against the United States".[1] The first solid-state phased array deployed[2] used a pair of Raytheon AN/FPS-115 phased array radar sets at each site[3] to cover an azimuth angle of 240 degrees. Two sites were deployed in 1980 at the periphery of the contiguous United States, then two more in 1987–95 as part of the United States Space Surveillance Network. One system was sold to Taiwan and is still in service.

Classification of radar systems

[edit]Under the Joint Electronics Type Designation System (JETDS), all U.S. military radar and tracking systems are assigned a unique identifying alphanumeric designation. The letters “AN” (for Army-Navy) are placed ahead of a three-letter code.[4]

- The first letter of the three-letter code denotes the type of platform hosting the electronic device, where A=Aircraft, F=Fixed (land-based), S=Ship-mounted, and T=Ground transportable.

- The second letter indicates the type of equipment, where P=Radar (pulsed), Q=Sonar, R=Radio, and Y=Data Processing

- The third letter indicates the function or purpose of the device, where G=Fire control, Q=Special Purpose, R=Receiving, S=Search, and T=Transmitting.

Thus, the AN/FPS-115 represents the 115th design of an Army-Navy “Fixed, Radar, Search” electronic device.[4][3]

Mission

[edit]

The radar was built in the Cold War to give early warning of a nuclear attack, to allow time for US bombers to get off the ground and land-based US missiles to be launched, to decrease the chance that a preemptive strike could destroy US strategic nuclear forces. The deployment of submarine launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) by the Soviet Union by the 1970s, significantly decreased the warning time available between the detection of an incoming enemy missile and its reaching its target, because SLBMs can be launched closer to the US than the previous ICBMs, which have a long flight path from the Soviet Union to the continental US. Thus there was a need for a radar system with faster reaction time than existing radars. PAVE PAWS later acquired a second mission of tracking satellites and other objects in Earth orbit as part of the United States Space Surveillance Network.

A notable feature of the system is its phased array antenna technology, it was one of the first large phased array radars. A phased array was used because a conventional mechanically-rotated radar antenna cannot turn fast enough to track multiple ballistic missiles.[5] A nuclear strike on the US would consist of hundreds of ICBMs and SLBMs incoming simultaneously. The beam of the phased array radar is steered electronically without moving the fixed antenna, so it can be pointed in a different direction in milliseconds, allowing it to track many incoming missiles at the same time.

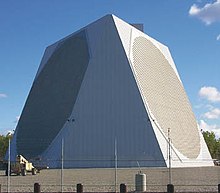

Description

[edit]The AN/FPS-115 radar consists of two phased arrays of antenna elements mounted on two sloping sides of the 105 ft high transmitter building, which are oriented 120° apart in azimuth.[6][5] The beam from each array can be deflected up to 60° from the array's central boresight axis, allowing each array to cover an azimuth angle of 120°, thus the entire radar can cover an azimuth of 240°. The building sides are sloped at an angle of 20°, and the beam can be directed at any elevation angle between 3° and 85°. The beam is kept at least 100 ft above the ground over public-accessible land to avoid the possibility of exposing the public to significant electromagnetic fields.

Each array is a circle 72.5 ft (22.1 m) in diameter consisting of 2,677 crossed dipole antenna elements, of which 1,792 are powered and serve as both transmitting and receiving antennas, with the rest functioning as receiving antennas. Due to the phenomenon of interference the radio waves from the separate elements combine in front of the antenna to form a beam. The array has a gain of 38.6 dB, and the width of the beam is only 2.2°. The drive current for each antenna element passes through a device called a phase shifter, controlled by the central computer. By changing the relative timing (phase) of the current pulses supplied to each antenna element the computer can instantly steer the beam to a different direction.

The radar operates in the UHF band between 420 - 450 MHz, which is shared with the 70 centimeter amateur band (just below the UHF television broadcast band), that is a wavelength of 71–67 cm, with circular polarization. It is an active array (AESA); each of the 1,792 transmitting elements has its own solid-state transmitter/receiver module, and radiates a peak power of 320 W, so the peak power of each array is 580 kW. It operates in a repeating 54 millisecond cycle in which it transmits a series of pulses, then listens for echoes. Its duty cycle (fraction of time spent transmitting) is never greater than 25% (so the average power of the beam never exceeds 25% of 540 kW, or 145 kW) and is usually around 18%. It is reported to have a range of about 3,000 nautical miles (3,452 statute miles, 5,555 km); at that range it can detect an object the size of a small car, and smaller objects at closer ranges.

The functioning of the radar is completely automatic, controlled by four computers. The software divides the beam time between "surveillance" and "tracking" functions, switching the beam back and forth rapidly between different tasks. In the surveillance mode, which normally consumes about 11% of the duty cycle, the radar repeatedly scans the horizon across its full 240° azimuth in a pattern between 3° and 10° elevation, creating a "surveillance fence" to immediately detect missiles as they rise above the horizon into the radar's field of view. In the tracking mode, which normally consumes the other 7% of the 18% duty cycle, the radar beam follows already-detected objects to determine their trajectory, calculating their launch and target points.

Background

[edit]

Fixed-reflector radars with mechanically-scanned beams such as the 1955 GE AN/FPS-17 Fixed Ground Radar and 1961 RCA AN/FPS-50 Radar Set were deployed for missile tracking, and the USAF tests of modified AN/FPS-35 mechanical radars at Virginia and Pennsylvania SAGE radar stations had "marginal ability" to detect Cape Canaveral missiles in summer 1962.[3] A Falling Leaves mechanical radar in New Jersey built for BMEWS successfully tracked a missile during the October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, and "an AN/FPS-85 long-range phased array (Passive electronically scanned array) radar was constructed at Eglin AFB"[3] Site C-6, Florida[7] beginning on 29 October 1962[8] (the Bendix Radio Division[9] FPS-85 contract had been signed 2 April 1962).[10] Early military phased array radars were also deployed for testing: Bendix AN/FPS-46 Electronically Steerable Array Radar (ESAR)[1] at Towson, MD[11] (powered up in November 1960),[12] White Sands' Multi-function Array Radar (1963), and the Kwajalein Missile Site Radar (1967).[13]

Submarine Launched Ballistic Missile Detection and Warning System

[edit]The Avco 474N Submarine Launched Ballistic Missile (SLBM) Detection and Warning System (SLBMD&W System)[14] was deployed as "an austere…interim line-of-sight system" after approval in July 1965[15] to modify some Air Defense Command (ADC) Avco AN/FPS-26 Frequency Diversity Radars into Avco AN/FSS-7 SLBM Detection Radars. The 474N sites planned for 1968 also were to include AN/GSQ-89 data processing equipment (for synthesizing tracks from radar returns), as well as site communications equipment that NORAD requested on 10 May 1965 to allow "dual full period dedicated data circuits" to the Cheyenne Mountain 425L System, which was "fully operational" on 20 April 1966.[15] (Cheyenne Mountain Complex relayed 474N data to "SAC, the National Military Command Center, and the Alternate NMCC over BMEWS circuits",[16] for presentation by Display Information Processors—impact ellipses and "threat summary display" with a count of incoming missiles[17] and "Minutes Until First Impact" countdown).[18]

By December 1965 NORAD decided to use the Project Space Track "phased-array radar at Eglin AFB…for SLBM surveillance on an "on-call" basis"[19] "at the appropriate DEFCON".[20] By June 1966 the refined FPS-85 plan was for it "to have the capability to operate in the SLBM mode simultaneously [sic] [interlaced transmissions] with the Spacetrack surveillance and tracking modes"[15] Rebuilding of the "separate faces for transmitting and receiving" began in 1967[21] after the under-construction Eglin FPS-85 was "almost totally destroyed by fire on 5 January 1965".[22] FPS-85 IOC was in 1969,[23] 474N interim operations began in July 1970 (474N IOC was 5 May 1972),[14] and in 1972 20% of Eglin FPS-85 "surveillance capability…became dedicated to search for SLBMs,"[24] and new SLBM software was installed in 1975.[12] (the FPS-85 was expanded in 1974).[21]

The Stanley R. Mickelsen Safeguard Complex with North Dakota phased arrays (four-face Missile Site Radar and single-face GE Perimeter Acquisition Radar, PAR) became operational in 1975 as part of the Safeguard Program for defending against enemy ballistic missiles.

Development

[edit]

The SLBM Phased Array Radar System (SPARS)[a] was the USAF program initiated in November 1972 by the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS)[26] while the Army's PAR was under construction. A 1974 SPARS proposal for "two new SLBM Phased Array Warning Radars" was submitted to replace the east/west coast 474N detection radars, which had "limitations against Soviet SLBMs, particularly the longer range SS-N-8"[27] on 1973 "Delta" class submarines.[21] Development began in August 1973,[28] SPARS was renamed[b] PAVE PAWS on 18 February 1975,[29]: 37 and system production was requested by a 13 June 1975 Request for Proposals (RFP).[1] Rome Air Development Center (RADC) "was responsible for the design, fabrication installation, integration test, and evaluation of" PAVE PAWS through 1980.[1]

The differing USAF AN/FPS-109 Cobra Dane phased array radar in Alaska achieved IOC on 13 July 1977[14] for "providing intelligence on Soviet test missiles fired at the Kamchatka peninsula from locations in southwestern Russia".[3] The Safeguard PAR station that closed in 1976, had its radar "modified for the ADCOM mission during 1977 [and] ADCOM accepted [the Concrete Missile Early Warning Station] from the Army on 3 October 1977"[14] for "SLBM surveillance of Arctic Ocean areas".[34] By December 1977 RADC had developed[1] the 322 watt PAVE PAWS "solid state transmitter and receiver module",[26] and the System Program Office (ESD/OCL) issued the AN/FPS-115 "System Performance Specification …SS-OCLU-75-1A" on 15 December 1977.[35] IBM's PAVE PAWS "beam-steering and pulse schedules from the CYBER-174" duplexed computers to the MODCOMP IV duplexed radar control computers were "based upon" PARCS program(s) installed for attack characterization in 1977 when the USAF received the Army's PAR.[26] Bell Labs enhanced[clarification needed] the PARCS beginning December 1978, e.g., "extending the range"[14] by 1989 for the Enhanced PARCS configuration (EPARCS).

Environmental and health concerns

[edit]USAF environmental assessments in August 1975 and March 1976 for PAVE PAWS were followed by the EPA's Environmental Impact Analysis in December 1977. Environmental impacts were litigated in U.S. District Court in Boston. The government asserted the position that Pave Paws would protect the American coastline, while hiding the fact that it had no defensive armaments in the event an incoming missile was detected.[26] The USAF requested the National Research Council (in May 1978) and a contractor, SRI International (April 1978), to assess PAVE PAWS radiation.[26] Two NRC reports were prepared (1979,[23] tbd), SRI's Environmental Impact Statement was reviewed during a 22 January 1979 public hearing at the Sandwich MA high school auditorium (~300 people).[29] The studies found no elevated cancer risk from PAVE PAWS[36] e.g., elevated Ewing sarcoma rates were not supported by 2005 available data[37] (a December 2007 MA Department of Health report concluded it "appears unlikely that PAVE PAWS played a primary role in the incidence of Ewing family of tumors on Cape Cod.")[38] A followup to a 1978 Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine report[39] concluded in 2005 that power densities beyond 15 metres (49.2 ft) were within permissible exposure limits.[40] Consistent with other regulations to prevent interference with aircraft systems, the FAA restricts aircraft at altitudes below 4,500 ft (1,400 m) to maintain 1 nm (1.85 km) from the Cape Cod SSPARS phased array.[41]

Deployment

[edit]

On May 23, 1975 the USAF announced the Raytheon Corporation would be contracted to build the East Coast facility in Otis Air Force Base and West Coast facility in Beale Air Force Base.[42][43] On October 27, 1976, ground-breaking ceremonies were held at the East Coast Site.[29]

System performance testing at the Otis facility began on April 3, 1978 and completed by January 16, 1979.[29] To mitigate interference at the FPS-115 site on Flatrock Hill[44] from the Cape & Islands Emergency Medical Service (CIEMSS), on 8 February 1979 ESD installed six high pass filters—then Raytheon was contracted 24 May to move the EMS Repeater Station to Bourne, Massachusetts (completed 13 July).[29] After a 5–7 March "final review of the East Coast PAVE PAWS EIS was held at Hq AFSC", the site was accepted by ESD on 12 April.[29] The "first radio frequency transmission" from the West Coast Site was 23 March 1979[29] (it was completed in October 1979).[5] "ADCOM wanted four [PAVE PAWS] sites, but by the end of 1979 only two had been funded".[14]

The Cape Cod system reached Initial operating capability (IOC) as the Cape Cod Missile Early Warning Station on 4 April 1981 with initial operational test and evaluation (IOT&E) completed 21 May;[14] Beale AFB reached IOC on 15 August.[45] The two PAVE PAWS, three BMEWS, and the PARCS & FPS-85 radar stations transferred to Strategic Air Command (then Space Command) in 1983.[23] By 1981 Cheyenne Mountain was providing 6,700 messages per hour[46] including those based on input from the PAVE PAWS and the remaining FSS-7 stations.[47] In 1981, as part of the Worldwide Military Command and Control System Information System (WIS), the Pentagon's National Military Command Center was receiving data "directly from the Satellite Early Warning System (SEWS) and directly from the PAVE PAWS sensor systems".[47]

Beam Steering Unit (BSU) and Receiver Beam Former (REX) replacements were made on the four Cape Cod and Beale radars in the 1980s.[48]

Expansion

[edit]The PAVE PAWS Expansion Program[29] had begun by February 1982 to replace "older FPS-85 and FSS-7 SLBM surveillance radars in Florida with a new PAVE PAWS radar to provide improved surveillance of possible SLBM launch areas southeast of the United States [and for another] to the Southwest."[34] After a 3 June 1983 RFP, Raytheon Company was contracted on 10 November and had a 22–23 February 1984 System Design Review for the Southeast and Southwest radars.[29] The Expansion's Development Test and Engineering testing commenced on 3 February 1986 at the Southeast Site (PAVE PAWS Site 3, Robins Air Force Base—completed 5 June) and 15 August at the Southwest Site (PAVE PAWS Site 4, Eldorado Air Force Station).[29] The Gulf Coast FPS-115s were operational in 1986 (Robins)[3] and May 1987 (Eldorado IOC).[45] In February 1995, all 4 radars were being netted by the "missile warning center at Cheyenne Mountain AS [which was] undergoing a $450 million upgrade program".[49] Other centers receiving PAVE PAWS output were the 19xx Missile Correlation Center and 19xx Space Control Center.[citation needed]

During the post-Cold War draw down, the Eldorado and Robins radar stations closed in 1995.[50] By October 1999, Cape Cod and Beale radars were providing data via Jam Resistant Secure Communication (JRSC) circuits to the Command Center Processing and Display System in the NMCC.[32] The transition of BMEWS and PAVE PAWS to SSPARS had begun with the 4 AN/FPS-50 BMEWS radars near Thule Air Base being replaced with a Raytheon AN/FPS-120 Solid State Phased Array Radar at Thule Site J (operational "2QFY87").[51]

In Taiwanese service

[edit]An AN/FPS-115 system was sold to Taiwan in 2000[52] and installed at Loshan or Leshan Mountain, Tai'an, Miaoli[53] in 2006. It was commissioned into service in 2013.[54] The system cost approximately US$1.4 billion and Raytheon was the prime contractor. It provides up to six minutes notice of Chinese ballistic missile attack. The system spends most of its time observing satellites and orbital debris; this information is shared with the United States.[55] In 2016 Raytheon Integrated Defense Systems was awarded a $26.2 million contract to upgrade Taiwan's radar system. This followed on a $289.5 million sustainment contract which Raytheon was awarded in 2012.[56] It has been reported that the defenses of Taiwan's PAVE PAWS system include a land based Phalanx CIWS.[57]

Taiwan had explored the acquisition of a second PAVE PAWS set but in 2012 decided against the purchase as the first PAVE PAWS set was significantly over budget and behind schedule. The second system would have been located in the south and together the PAVE PAWS sets would have provided Taiwan with 360-degree coverage.[58]

The radar site in Taiwan sits on top of a mountain at an elevation of over 2,600 m (8,500 ft).[59] Due to its extremely elevated position the Taiwanese set has the unique ability to track surface ships. Detection and tracking data is believed to be shared with the United States in real time; this has not been officially confirmed.[60]

The radar site was first occupied by a Naval Maritime and Surveillance Command radar surveillance facility, which was relocated to a higher peak in the same region to make way for PAVE PAWS.[61]

Replacement

[edit]

The Solid State Phased Array Radar System (SSPARS) began replacing PAVE PAWS when the first AN/FPS-115 face was taken off-line for the radar upgrade. New Raytheon AN/FPS-123 Early Warning Radars became operational in 19xx (Beale) and 19xx (Cape Cod) in each base's existing PAVE PAWS "Scanner Building".[21] RAF Fylingdales, UK and Clear Space Force Station, Alaska BMEWS stations became SSPARS radar stations when their respective AN/FPS-126 radar (3 faces)[63] and 2001 Raytheon AN/FPS-120 Solid State Phased Array Radar became operational.[62] In 2007, 100 owners/trustees of amateur radio repeaters in the 420 to 450 MHz band near AN/FPS-123 radars were notified to lower their power output to mitigate interference,[64] and AN/FPS-123s were part of the Air Force Space Surveillance System by 2009.[65] The Beale AN/FPS-123 was upgraded to a Raytheon AN/FPS-132 Upgraded Early Warning Radar (UEWR), circa 2012, with capabilities to operate in the Ground-based Midcourse Defense (GMD) ABM system—the Beale UEWR included Avionics, Transmit-Receive modules,[30] Receiver Exciter / Test Target Generator, Beam Steering Generator, Signal Processor, and other changes.[66] After additional UEWR installations for GMD at Thule Site J and the UK (contracted 2003[43]), a 2012 ESD/XRX Request for Information for replacement, and remote operation, of the remaining "PAVE PAWS/BMEWS/PARCS systems" at Cape Cod, Alaska, and North Dakota was issued.[48] The Alaska AN/FPS-132 was contracted in fall 2012[67] and in 2013, the U.S. announced a plan to sell an AN/FPS-132 to Qatar.[68]

See also

[edit]- Dunay radar, a UHF radar with a similar function and era of development.

- Voronezh radar, the latest post Soviet-era Russian equivalent.

- List of military electronics of the United States

Notes

[edit]- ^ PAVE PAWS was one of the earliest large USAF Support Systems not developed with a 3 digit number and an appended letter, such as the preceding 474N SLBM system and the "Big L" systems that included the Burroughs "425L Command/Control and Missile Warning" ("fully operational" at Cheyenne Mountain on 20 April 1966[15]) and the "496L Spacetrack" systems[25] which networked PAVE PAWS.

- ^ The PAVE identifier used when PAVE PAWS was designated on 18 February 1975[29]: 37 was "a code word for the Air Force unit in charge of the project" and which developed other PAVE systems—"CF" the unit for "the COBRA system" with[3] the Cobra Dane (AN/FPS-108) radar. By 1979, PAVE systems used the term Precision Acquisition Vehicle Entry defined for the identifier, e.g., the 1980 PAVE Pillar[30][failed verification] and c. 1977[1] Pave Mover (JSTARS) programs initiated by the USAF.[31] In particular, on 1 October 1999 the Department of the Air Force identified PAVE PAWS as "Precision Acquisition Vehicle Entry Phased Array Warning System",[32] a term publicized as early as 1979.[33]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Smith, John Q.; Byrd, David A (1991). Forty Years of Research and Development at Griffis Air Force Base: June 1951 – June 1991 (Report). Rome Laboratory. Archived from the original on 8 April 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2014. (PAVE PAWS concept drawing on p. 141)

- ^ Brookner, Eli (1 May 1997). "Major Advances in Phased Arrays: Part 1". The Microwave Journal. Horizon House Publications.

diameter of 102 feet for a total of approximately 5300 elements. The elements in this outer ring beyond the 72.5 feet are reserved for a future 10 dB increase in system sensitivity.

- ^ a b c d e f g Winkler, David F. (1997). "Radar Systems Classification Methods". Searching the Skies: The Legacy of the United States Cold War Defense Radar Program (PDF). Langley AFB, Virginia: United States Air Force Headquarters Air Combat Command. p. 73. LCCN 97020912.

- ^ a b Avionics Department (2013). "Missile and Electronic Equipment Designations". Electronic Warfare and Radar Systems Engineering Handbook (PDF) (4 ed.). Point Mugu, California: Naval Air Warfare Center Weapons Division. pp. 2–8.1.

- ^ a b c "AN/FPS-115 PAVE PAWS Radar". Space Systems. GlobalSecurity.org. 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ National Missile Defense Deployment - Final Environmental Impact Statement, Vol. 4. United States Army Space and Missile Defense Command. July 2000. pp. H.1.4–H.1.9.

- ^ "20th Space Control Squadron". Archived from the original on 28 December 2010. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "National Security Space Road Map – Eglin". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 9 April 2015.

- ^ "Bendix workers at work during construction of a 13-storey structure for the AN/FPS-85 radar at Eglin AFB, United States". US Air Force via criticalpast.com. 1965.

A man surveying and aligning each member on the 45DG scanner face with delicate optical equipment.

{{cite web}}: External link in|quote= - ^ NORAD Historical Summary January-June 1962 (PDF), 1 November 1962

- ^ "Animation shows the functioning and working of the AN/FPS-85 Spacetrack Radar in Florida, United States". US Air Force via criticalpast.com. 1965.

- ^ a b "AN/FPS-85 Spacetrack Radar". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ "US Secretary of Defense Testifies". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 23 (6): 23. June 1967. Bibcode:1967BuAtS..23f..21.. doi:10.1080/00963402.1967.11455087. ISSN 0096-3402.

- ^ a b c d e f g "IV. Ballistic Missile Surveillance and Warning". History of ADCOM January 1977 to December 1978. p. 87.

Normally, the radar worked on commercial power, but six diesel generators had been provided for backup in case that source was disrupted. For the radar's energy pulse to reach out to its maximum range, electrical power was drawn into a capacitor bank, built up, then discharged or surged into space. This procedure, called power surging happened every 51 milliseconds. … reviewed plans for EPARCS and they had concluded its location limited its ability to provide adequate warning of low angle trajectory ICBM reentry vehicles … About a 24 percent reduction in [Thule] O&M costs would be realized using an upgraded PAVE PAWS[-type] phased array.

- ^ a b c d NORAD Historical Summary January – December 1966 (PDF), US Air Force, 1 May 1967,

on 22 June 1965 the JCS directed CONAD to prepare a standby plan for use of the USAF AN/FPS-85 facility at Eglin AFB as a backup to the SDC, and an interim backup plan for use in the event of catastrophic failure prior to availability of the AN/FPS-85. An interim backup plan was submitted to the JCS in August 1965 and was approved on 12 October. This plan, 393C-65, was published on 15 November 1965. A draft plan for use of the AN/FPS-85 had also been submitted to the JCS in August 1965. This plan was approved on 21 October 1965. It was published as Operations Plan 392C-66 on 10 October 1966 and was to be implemented on the FOC date of the AN/FPS-85.

- ^ "NORAD Historical Summary (July-December 1965)" (PDF). 1 May 1966.

The Spacetrack radar at Moorestown and the cooperating radar at Trinidad were not to be closed until the FPS-85 at Eglin AFB proved its operational capability. … By 20 October, U.S. -U.K. agreement had been reached to let the U.K. Operations Centre pass BMEWS warning data to SHAPE. … Satellite Reconnaissance Advance Notice (SATRAN), was developed jointly by DIA, the Foreign Technology Division, and NORAD. …commanders would be able to plot the track of a satellite over their areas and take defensive action, such as dispersal, camouflage, etc.

- ^ "NORAD Center Located at Colorado Springs Site" (Google news archive). The Othello Outlook. 26 November 1964. p. 3. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew (17 June 1964). "The Doomsday Men". The Age.

- ^ "NORAD Historical Summary January – December 1966" (PDF). US Air Force. 1 May 1967.

AN/GSQ-89 (SLBM Detection and Warning System) … On 31 July 1964, NORAD concurred with the main conclusions of the study. NORAD recommended to USAF that funds for an austere interim system… DDR&E approved the interim line-of-sight system concept on 5 November 1964 and made $20.2 million available for development. The SLBM Contractor Selection Board, with NORAD representation, recommended the selection of the AVCO Corporation. In July 1965, DDR&E approved AVCO's plan to modify FPS-26 height finder radars at six sites and to install one at Laredo AFB, Texas (Laredo would then be designated site Z-230). … The modified radars were to be termed AN/FSS-7's and the system was to be designated the AN/GSQ-89.

- ^ Leonard, Barry (2009). History of Strategic Air and Ballistic Missile Defense (PDF). Vol. II, 1955–1972. Fort McNair, DC: Center for Military History. ISBN 978-1-4379-2131-1. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Photographs / Written Historical and Descriptive Data: Cape Cod Air Station Technical Facility/Scanner Building and Power Plant (PDF) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

Technical Facility/Scanner Building (HAER No. MA-151-A), which houses the AN/FPS-1152 radar and related equipment… PAVE PAWS Site 1 … AN/FSS-7…designed by Avco Electronics Division… The first two PAVE PAWS sites in Massachusetts and California represented the first two-faced phased array radars deployed by the U.S.

- ^ NORAD Historical Summary July-December 1964 (PDF), US Air Force, 31 March 1965

- ^ a b c "Brief History of Aerospace Defense Command" (transcript of USAF document). Histories for HQ Aerospace Defense Command, Ent AFB, Colorado. Military.com Unit Pages. 1972.

AN/FSS-7 radars located on the Atlantic, Pacific and Gulf coasts. The network, eventually controlled by the 4783rd Surveillance Squadron of the 14th [sic] Aerospace Force, was fully operational by May 1972. … On 11 September 1978, Air Force Secretary John Stetson, at the urging of Under Secretary Hans Mark, had authorized a "Space Missions Organizational Planning Study" to explore options for the future. When published in February 1979, the study had offered five alternatives ranging from continuation of the status quo to creation of an Air Force command for space.

- ^ Jane's Radar and Electronic Systems, 6th edition, Bernard Blake, ed. (1994), p. 31

- ^ "NORAD's Information Processing Improvement Program: Will It Enhance Mission Capability?" (Report to Congress). Comptroller General. 21 September 1978. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Engineering Panel on the PAVE PAWS Radar System (1979). Radiation Intensity of the PAVE PAWS Radar System (PDF) (Report). National Academy of Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

The [Cape Cod] PAVE PAWS antenna consists of a circular array of 5,354 elements, of which only half, or 2,677, are to be active when the facility begins operation in April 1979, and of the active elements only 1,792 are powered. At some future date, which is not yet determined, the entire antenna may be placed in operation. The beam of radiation is focused and pointed in a specific direction by controlling the way the individual elements radiate. If the beam is to be directed to the left of center (or "boresight"), the signals radiated from the elements on the left side of the array are delayed relative to those emitted from the elements on the right, the period of the delay increasing progressively across the array from right to left.

- ^ "Documents on Disarmament – Report by Secretary of Defense Schlesinger to Congress". United Nations. 1974. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

The Western hemisphere satellites provide the first warning of SLBM launches against the U.S. Complementary warning coverage is now supposed to be provided by the 474N SLBM "dish" warning radars. Unfortunately, these 474N radars—four on the East Coast, three on the West Coast, and one on the Gulf Coast—have limitations against Soviet SLBMs, particularly the new longer range SS-N-8. … Accordingly, we again propose to replace those radars (including the AN/FPS-49 standby SLBM warning radar at Moorestown, New Jersey) with two new SLBM Phased Array Warning Radars—one on the East Coast and one on the West Coast.

- ^ Satterthwaite, Charles P. (June 2000). "Space Surveillance And Early Warning Radars: Buried Treasure for the Information Grid" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2015.

The network, eventually controlled by the 4783rd Surveillance Squadron of the 14th [sic] Aerospace Force, was fully operational by May 1972. … Early Warning Radar Systems such as PARCS and PAVE PAWS, and Space Surveillance Radars, such as the Eglin AFB Radar…are called Buried Treasure, because they already exist as National Information Source assets, but their full potential and value is greatly under utilized.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Del Papa, Dr. E. Michael; Warner, Mary P (October 1987). A Historical Chronology of the Electronic Systems Division 1947–1986 (PDF) (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

the Space Defense Center combining the Air Force's Space Track and the Navy's Spasur.

- ^ a b "Northrop Grumman Sets T/R Module Standard". Avionics Today. 12 April 2011.

- ^ Levis, Alexander H. (ed.). The Limitless Sky (PDF). p. 74.

- ^ a b Communications-Electronics (C-E) Manager's Handbook (PDF) (Report). Department of the Air Force. 1 October 1999. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

The NMCC's [Command Center Processing and Display System] provides Tactical Warning and Attack Assessment (TW/AA) data to surveillance officers in the Emergency Actions Room and the National Military Intelligence Center (NMIC).

- ^ "Pave Paws for the Cape". The Telegraph. 23 January 1979.

- ^ a b Weinberger, Caspar; SECDEF (8 February 1982). Annual Report to Congress: Fiscal Year 1983 (PDF) (Report). United States Department of Defense. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- ^ System Performance Specification for Phased Array Warning System, PAVE PAWS, Radar Set AN/FPS-115, Hanscom Air Force Base: Prepared by PAVE PAWS System Program Office, Electronic Systems Division, OCL, 15 December 1977 (cited by ADA088323)

- ^ Cape radar found not to pose health risk Accessed 5 November 2007

- ^ National Academies' National Research Council. Available Data Do Not Show Health Hazard to Cape Cod Residents From Air Force PAVE PAWS Radar. January 2005.

- ^ "Evaluation of the Incidence of the Ewing's Family of Tumors on Cape Cod, Massachusetts and the PAVE PAWS Radar Station" (PDF). Massachusetts Department of Health. December 2007.

- ^ "Environmental Check to Precede Otis Radar". The Telegraph. 12 April 1978.

- ^ "2005 Radio Frequency Power Density Survey for the Precision Acquisition Vehicle Entry-Phased Array Warning System (PAVE PAWS), Cape Cod AFS, MA" (PDF). US Air Force. 23 December 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011.

- ^ FAA – SNY – New York – Sectional Aeronautical Chart Edition 86 – 15 November 2012

- ^ "Otis Air Base Selected for New Radar Site". The Telegraph. 28 May 1975.

- ^ a b "Brochure – History of Cape Cod Air Force Station" (PDF). Air Force via radomes.org. 10 January 2008.

- ^ "Test Report with Appendices" (PDF). Broadcast Signal Lab via isotrope.im. June 2004.

- ^ a b Cold War Historic Properties of the 21st Space Wing Air Force Space Command (PDF) (Report). OSTI.gov. 1996. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

Cold War era (36 CFR 60.4)

- ^ "minutes of "hearings before a subcommittee of the Committee on Government Operations, House of Representatives, Ninety-seventh Congress; 19 and 20 May 1981"". Failures of the North American Aerospace Defense Command's (NORAD) attack warning system (Report). United States Government Printing Office. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

at Norad is the establishment of a Systems Integration Office

- ^ a b Modernization of the WWMCCS Information System (WIS) (PDF) (Report). Armed Services Committee, US House of Representatives. 19 January 1981. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ a b PAVE PAWS, BMEWS, and PARCS Radar Systems (Solicitation), FedBizOpps.gov, 23 January 2012, retrieved 11 June 2014,

The PAVE PAWS and BMEWS Beam Steering Unit (BSU), Receiver Exciter (REX), Receiver Beam Former (RBF), Array Group Driver (AGD), Radio Frequency Monitor (RFM), Frequency Time Standard (FTS), and the Corporate Feed (CFD) were built for these five radars in the late 1970s and were upgraded in the 1980s… The PARCS Signal Processing Group (SPG) has received only "band-aid" fixes since the site's Initial Operating Capability (IOC) in 1975

- ^ Orban, SSgt. Brian (February 1995). "The trip wire". The Guardian. Air Force Space Command. p. 6.

For more than 30 years, the crews operating the missile warning center inside Cheyenne Mountain have maintained an early warning trip line [for] incoming ballistic missiles

- ^ "PAVE PAWS Site". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 22 February 2016.

- ^ "National Security Space Road Map – Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMEWS) at Clear". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016.

- ^ "Fact Sheet – Upgraded Early Warning Radars, AN/FPS-132" (PDF). US Air Force. 15 January 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 September 2014.

- ^ Fisher Jr, Richard D (5 June 2014). "New Chinese radar may have jammed Taiwan's SRP". IHS Jane's Defence Weekly.

- ^ "A Dossier on the Pave Paws Radar Installation on Leshan, Taiwan" (PDF). Federation of American Scientists. 8 March 2013.

the ITT Exelis Electronic Systems segment in Clifton, N.J., is the prime sustainment and modernization contractor for these radar systems. … PARCS…analyzes more than 20,000 tracks per day, from giant satellites to space debris.

- ^ ACKERMAN, SPENCER. "Taiwan's Massive, Mega-Powerful Radar System Is Finally Operational". Wired. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Keller, John (30 November 2016). "Raytheon to upgrade Taiwan missile-defense surveillance radar to mitigate obsolescence issues". Military & Aerospace Electronics. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Trevithick, Joseph (14 August 2019). "Taiwan Reveals Land-Based Variant of Naval Point Defense Missile System To Guard Key Sites". The Drive. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ "Taiwan scraps plan to buy US-made long-range radar". Bangkok Post. Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Charlier, Phillip (13 October 2020). "President visits long-range, early-warning station: Media speculates on US personnel spotted in the background". Taiwan English News. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Chen, Kelvin (30 November 2020). "Military scholar highlights importance of Taiwan's Leshan radar station". Taiwan News. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Chin, Jonathan (16 October 2018). "Navy radar station guards west coast from mountain top". Taipei Times. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Raytheon completes upgrades to BMEWS radar in Alaska". radomes.org. 16 March 2001.

...relocation of existing electronic equipment from a decommissioned PAVE PAWS site in Eldorado, Texas, to the newly constructed facility at Clear. By relocating the two 102-foot diameter transmitter/receiver arrays, electronic cabinets and computers

- ^ "AN/FPS-115, AN/FPS-120, AN/FPS-123, AN/FPS-126". Radomes.org. Archived from the original on 17 February 2014. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ^ "Amateur Radio Repeaters Interfering with Government Radar". W5YI.org. 8 July 2007.

- ^ Chatters, Maj Edward P IV; Crothers, Maj Brian J. (2009). "Chapter 19: Space Surveillance Network" (PDF). AU-18 Space Primer (PDF). Air University. p. 252. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

Perimeter Acquisition Vehicle Entry Phased-Array Weapons System (PAVE PAWS)

- ^ "Contract HQ0006-01-C-0001" (PDF). dod.mil. 1 January 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2013.

- ^ "PAVE PAWS Radar Upgrades: Clear AFS Goes from Warning to BMD Targeting". Defense Industry Daily. 17 September 2012.

- ^ "U.S. to Sell Large Early Warning Radar to Qatar". MostlyMissileDefense.com. 7 August 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

External links

[edit]| External images | |

|---|---|

- "Pave Paws – Fact Sheet". afspc.af.mil.

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) documentation, filed under End of Spencer Paul Road, north of Warren Shingle Road (14th Street), Marysville, Yuba County, CA:

- HAER No. CA-319, "Beale Air Force Base, Perimeter Acquisition Vehicle Entry Phased-Array Warning System (PAVE PAWS)", 13 photos, 56 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- HAER No. CA-319-A, "Beale Air Force Base, PAVE PAWS, Technical Equipment Building", 15 photos, 9 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- HAER No. CA-319-B, "Beale Air Force Base, PAVE PAWS, Power Plant", 5 photos, 5 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. CA-319-C, "Beale Air Force Base, PAVE PAWS, Guard Tower", 3 photos, 4 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. CA-319-D, "Beale Air Force Base, PAVE PAWS, Bus Shelter", 4 data pages

- HAER No. CA-319-E, "Beale Air Force Base, PAVE PAWS, Gate House", 3 photos, 4 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. CA-319-F, "Beale Air Force Base, PAVE PAWS, Civil Engineering Storage Building", 2 photos, 4 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. CA-319-G, "Beale Air Force Base, PAVE PAWS, Emergency Generator Enclosure", 2 photos, 4 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. CA-319-H, "Beale Air Force Base, PAVE PAWS, Clean Lubrication Oil Storage Tank and Enclosure", 2 photos, 4 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. CA-319-I, "Beale Air Force Base, PAVE PAWS, Supply Warehouse", 20 photos, 4 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. CA-319-J, "Beale Air Force Base, PAVE PAWS, Microwave Equipment Building", 2 photos, 4 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. CA-319-K, "Beale Air Force Base, PAVE PAWS, Electric Substation", 1 photo, 4 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. CA-319-L, "Beale Air Force Base, PAVE PAWS, Satellite Communications Terminal", 3 photos, 4 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- 1978 establishments in the United States

- United States Space Surveillance Network

- Radars of the United States Air Force

- Computer systems of the United States Air Force

- Historic American Engineering Record in California

- Military equipment of the Republic of China

- Military equipment introduced in the 1980s

- Military electronics of the United States