Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans

Archdiocese of New Orleans Archidioecesis Novae Aureliae Archidiocèse de La Nouvelle-Orléans | |

|---|---|

Cathedral Basilica of St. Louis | |

Coat of arms | |

| Location | |

| Country | |

| Territory | |

| Episcopal conference | United States Conference of Catholic Bishops |

| Ecclesiastical region | V |

| Ecclesiastical province | New Orleans |

| Statistics | |

| Area | 4,208 sq mi (10,900 km2) |

| Population - Total - Catholics | (as of 2013) 1,238,228 520,056 (42%) |

| Parishes | 107 |

| Churches | ~137 |

| Schools | +25 |

| Information | |

| Denomination | Catholic Church |

| Sui iuris church | Latin Church |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Established | April 25, 1793 |

| Cathedral | Cathedral Basilica of Saint Louis |

| Patron saint | |

| Secular priests | 387 |

| Current leadership | |

| Pope | Francis |

| Archbishop | Gregory Michael Aymond |

| Bishops emeritus | Alfred Clifton Hughes |

| Map | |

| |

| Website | |

| arch-no.org | |

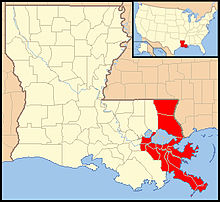

The Archdiocese of New Orleans (Latin: Archidioecesis Novae Aureliae, French: Archidiocèse de la Nouvelle-Orléans, Spanish: Arquidiócesis de Nueva Orleans) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical division of the Catholic Church spanning Jefferson (except Grand Isle),[1] Orleans, Plaquemines, St. Bernard, St. Charles, St. John the Baptist, St. Tammany, and Washington civil parishes of southeastern Louisiana. It is the second to the Archdiocese of Baltimore in age among the present dioceses in the United States, having been elevated to the rank of diocese on April 25, 1793, during Spanish colonial rule.

Its patron saints are the virgin Mary under the title of Our Lady of Prompt Succor and St. Louis, King of France, and Cathedral Basilica of Saint Louis is its mother church with St. Patrick's Church serving as a pro-cathedral. The archdiocese has 137 church parishes administered by 387 priests (including those belonging to religious institutes), 187 permanent deacons, 84 brothers, and 432 sisters. There are 372,037 Catholics on the census of the archdiocese, 36% of the total population of the area. The current head of the archdiocese is Archbishop Gregory Michael Aymond.

The Archdiocese of New Orleans reflects the cultural diversity of the city of New Orleans and the surrounding (civil) parishes. As a major port, the city has attracted immigrants from around the world. When French and Spanish Catholics ruled the city, some encouraged enslaved Africans to adopt Christianity, resulting in a large population of African American Catholics with deep heritage in the area. Later, Irish, Italian, Polish, Bavarian, and other immigrants have brought their heritage and customs to the archdiocese. The last quarter of the 20th century also brought many Vietnamese Catholics from South Vietnam to settle in the city. New waves of immigrants from Mexico, Honduras, Nicaragua and Cuba also have added to the Catholic population.

The Archdiocese of New Orleans is also a metropolitan see of a province that spans the entire U.S. state of Louisiana. Its suffragan sees are the Diocese of Alexandria, Diocese of Baton Rouge, Diocese of Houma-Thibodaux, Diocese of Lafayette in Louisiana, Diocese of Lake Charles, and Diocese of Shreveport. As of June 2023[update] the archdiocese is under chapter 11 bankruptcy due to the mounting cost of litigation around cases of sexual abuse by clerics of the diocese and coverups, and covid.[2]

History

[edit]

The Catholic Church has had a presence in New Orleans since before the founding of the city by the French in 1718. Missionaries served the French military outposts and worked among the native peoples. The area was then under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Quebec. In 1721 Fr. Francis-Xavier de Charlevoix, S.J., made a tour of New France from the Lakes to the Mississippi, and visiting New Orleans, he describes "a little village of about one hundred cabins dotted here and there, a large wooden warehouse in which I said Mass, a chapel in course of construction and two storehouses".[3]

In 1722 the Capuchins were assigned ecclesiastical responsibility for the Lower Mississippi Valley, while the Jesuits maintained a mission, based in New Orleans, to serve the indigenous peoples. The Jesuit vicar-general returned to France to recruit priests and also persuaded the Ursulines of Rouen to assume charge of a hospital and school. The royal patent authorizing the Ursulines to found a convent in Louisiana was issued September 18, 1726. Ten religious from various cities sailed from Hennebont on January 12, 1727, and reached New Orleans on August 6. As the convent was not ready, the governor gave up his residence to them. They opened a hospital for the care of the sick and a school for poor children.[3]

France surrendered New Orleans and the rest of Louisiana Territory west of the Mississippi to the Spanish under the Treaty of Paris of 1763. From then until 1783, East Florida and West Florida were under British control, but both Florida colonies reverted to Spain as part of the Peace of Paris in 1783. Pope Pius VI erected the Diocese of Louisiana and the Two Floridas encompassing the pioneer parishes of New Orleans and Louisiana and both Florida colonies on April 25, 1793, taking its territory from the Diocese of San Cristobal de la Habana, based in Havana, Cuba. The diocese originally encompassed the entire territory of the Louisiana Purchase, from the Gulf of Mexico to British North America, as well as the Florida peninsula and the Gulf Coast.[3] This date of erection makes the present Archdiocese of New Orleans the second oldest Catholic diocese in the present United States after the Archdiocese of Baltimore, which the same pope had erected as the Diocese of Baltimore on November 6, 1789. The new diocese encompassed the area claimed by Spain as Louisiana, which was all the land draining into the Mississippi River from the west, as well as Spanish territory to the east of the river in modern-day Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida.

In April 1803, the United States purchased Louisiana from France, which had in 1800 forced Spain to retrocede the territory in the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso. The United States took formal possession of New Orleans on December 20, 1803, and of Upper Louisiana on March 10, 1804. John Carroll, the Bishop of Baltimore, served as apostolic administrator of the diocese from 1805 to 1812. The diocese became a suffragan of the see of Baltimore, which had been elevated to a metropolitan archdiocese in 1808, during this period. Archbishop Carroll's successor as apostolic administrator would eventually be the diocese's first resident bishop of the 19th century.

In 1823, Pope Pius VII appointed Joseph Rosati to the office of coadjutor bishop of the diocese. At the diocesan bishop's suggestion, the diocesan bishop was based in New Orleans while his coadjutor was based in St. Louis.

On 19 August 1825, Pope Leo XII erected the Apostolic Vicariate of Alabama and the Floridas, taking its territory from the Archdiocese of Louisiana and the Two Floridas. Although the two Florida territories were no longer part of the diocese, he did not change its title. But soon after, Bishop Rosati abruptly resigned the office of coadjutor bishop during a trip to Rome after which the Vatican decided to split the diocese again, making St. Louis a separate see. On 18 July 1826, the same pope

- Erected the Diocese of St. Louis, taking its territory from the Diocese of Louisiana and the Two Floridas and the Diocese of Durango,

- Erected the Apostolic Vicariate of Mississippi, taking its territory from the Diocese of Louisiana and the Two Floridas,

- Changed the title of the Diocese of Louisiana and the Two Floridas to Diocese of New Orleans, and

- Appointed Bishop Rosati as apostolic administrator of both the Diocese of New Orleans and the new Diocese of St. Louis.

On 19 July 1850, Pope Pius IX erected the Apostolic Vicariate of the Indian Territory East of the Rocky Mountains. On the same day, he elevated the Diocese of New Orleans to a metropolitan archdiocese.

On 29 July 1953, Pope Pius IX erected the Diocese of Natchitoches, taking its territory from the archdiocese and making it a suffragan of the same metropolitan see.

On 11 January 1918, Pope Benedict XV erected the Diocese of Lafayette in Louisiana, taking its territory from the archdiocese making it a suffragan of the same metropolitan see.

On 22 July 1961, Pope John XXIII erected the Diocese of Baton Rouge, taking its territory from the archdiocese and making it a suffragan of the same metropolitan see.

On 2 March 1977, Pope Paul VI erected the Diocese of Houma-Thibodaux, taking its territory from the archdiocese and making it a suffragan of the same metropolitan see.

In its long history, the archdiocese and the city of New Orleans have survived several major disasters, including several citywide fires, a British invasion, the American Civil War, multiple yellow fever epidemics, anti-immigration and anti-Catholicism, the New Orleans Hurricane of 1915, Segregation, Hurricane Betsy, and an occasional financial crisis, not to mention Hurricane Katrina. Each time, the archdiocese rebuilt damaged churches and rendered assistance to the victims of every disaster. More recently, the church has faced an increased demand for churches in the suburbs and a decline in attendance to inner-city parishes. The church has also weathered changes within the Catholic Church, such as the Second Vatican Council, and changing spiritual values throughout the rest of the United States.[4]

The archdiocese sustained severe damage from Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita. Numerous churches and schools were flooded and battered by hurricane-force winds. In the more heavily flooded neighborhoods, such as St. Bernard Parish, many parish structures were wiped out entirely.[5]

Response to same-sex marriage

[edit]In early 2009, the state of Maine passed a law allowing same-sex civil marriage. In July 2009, the Archdiocese of New Orleans contributed $2,000 to a referendum campaign to overturn that law.[6] According to Maine's "Commission on Governmental Ethics & Election Practices", the Diocese of Portland Maine spent over $553,000 to overturn the law.[7]

Sex abuse scandal and 2020 bankruptcy filing

[edit]In November 2018, after consulting with community and civic leaders, the Archdiocese of New Orleans listed 81 clergy who were "credibly accused" of committing acts of sex abuse over decades while they were serving in the archdiocese.[8][9][10] Some settled lawsuits filed against them while one, Francis LeBlanc, had been convicted[8] in 1996.

In December 2019, former deacon Greg Brignac was arrested for multiple acts of abuse, including raping an altar boy at Our Lady of the Rosary Parish in the late 1970s.[11] Brignac died before his trial, shortly after falling and breaking his back in jail in June 2020.[12][13][14]

In January 2020, the New Orleans Saints football team said that Senior Vice President for Communications Greg Bensel had provided public relations advice to the archdiocese. Bensel gave them "...input on how to work with the media" regarding the sex abuse scandal.[9] He advised the archdiocese to "Be direct, open and fully transparent, while making sure that all law enforcement agencies were alerted."[9][10]

On May 1, 2020, the archdiocese filed for chapter 11 bankruptcy, affecting only the administrative office of the archdiocese, and not schools, Masses, and other ministries, citing the mounting cost of litigation from sexual abuse cases and the unforeseen financial consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.[15] The archdiocese, which had a $45 million budget,[16] owed $38 million in bonds to creditors and was also facing more pending sex abuse lawsuits.[16][17] The pending sex abuse lawsuits, which were suspended due to the bankruptcy filing,[17] would probably have cost the already financially struggling archdiocese millions of dollars more.[16] On August 20, 2020, victims of sex abuse by clergy who served in the archdiocese filed a motion in court to dismiss the bankruptcy.[18] The case continued as of June 2023[update].[2]

In May 2020, the board president of an archdiocesan ministry, who chose to remain anonymous, resigned his post. He claimed that he was forced out of his position because he was suing the archdiocese. In 2013, the man had told Archbishop Aymond that he had been molested in 1980 at St. Ann School in Metairie by archdiocesan priest James Collery. Collery died in 1987.[19] In 2013, Aymond agreed to pay for the victim's counseling as needed. In 2019, this agreement was amended to cover six more years of counseling.[19] However, the victim sued the archdiocese in April 2020, saying that he took this action after discovering that Collery had had other victims.[19]

Also in May 2020, U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Meredith Grabill suspended all archdiocesan retirement benefits for priests credibly accused of sexually abusing minors.[20] One of the priests, Paul Calamari, petitioned the court to reinstate his benefits. Speaking in a court session, Calamari told Grabill that he had a "failing" and a "sin" with a 17-year-old high school boy in 1973.[20] In November, 2020, a news report revealed that the archdiocese had paid one of Calamari's alleged victims US$100,000 two years before, deeming the sex abuse allegations against Calamari to be credible.[21][22]

On August 19, 2020, Brian Highfill was added to the archdiocesan list of credibly accused clergy, nearly two decades after he was first accused of sex abuse.[23] A trove of love letters which Highfill wrote to one of his victims, Scot Brander, in the 1980s also backed allegations that he committed acts of sex abuse.[23] Brander, who Highfill had known since he was ten, later committed suicide; his brother Michael Brander kept the letters and still pursued justice.[23] The archdiocese refused until 2018 to deem sex abuse allegations against Highfill as credible, but then suspended him indefinitely from ministry;[23] his was the 64th name added to the 2018 list of credibly accused clergy.[18] Highfill, who was also accused of committing sexual abuse against two airmen while serving as an Air Force chaplain in the Archdiocese for the Military Services, died of cancer in January 2022 while still undergoing a criminal investigation by the U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations.[24]

On October 23, 2020, archdiocesan priest Pat Wattigny was arrested in Georgia on a warrant issued by the St. Tammany Parish Sheriff's office,[25] charged with four counts of molestation of a juvenile, sexual abuse of a teenage boy, while he was leading a church in Slidell.[25] Wattigny allegedly confessed to the Archdiocese of New Orleans that he had started sexually abusing his victim in 2013.[25]

In June 2023 it was revealed by hitherto secret church files—the district attorney refused to say whether a subpoena had been issued for the documents—that the last four archbishops of New Orleans had gone to "shocking lengths" to hide child abuse by a confessed molester who was still alive at the time. Priest Lawrence Hecker confessed to his superiors in 1999 that he had between about 1966 and 1979 sexually molested several teenagers that he had met due to his work as a priest. Hecker's confession said that Archbishop Philip Hannan spoke with him in 1988 about an accusation of sexual abuse. In 1996 Hannan's successor Francis Schulte deemed another allegation as unsubstantiated. Hecker was allowed to continue working until he retired in 2002.[26][27]

In the aftermath of the 2002 sexual abuse scandal in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Boston, attorneys for the archdiocese, pressured by the scandal, reported Hecker, and a few other priests, to the New Orleans police, but only mentioned one case, and not that he had confessed. Hecker was never charged with a crime, although further accusations were made over time. The Catholic church adopted transparency policies after the Boston scandal, but the New Orleans archdiocese only acknowledged that Hecker was a predator on releasing the 2018 list of accused clergy. In early 2020, despite his having confessed to child abuse, the Vatican bestowed the honorific title of monsignor on Hecker.[28]

The diocese continued paying Hecker and other abusers retirement benefits, until a judge overseeing the diocese's bankruptcy ordered payments to stop. It was not clear in June 2023, when the documents became public, whether Hecker, aged 91, would be charged.[26][27] In August 2023, Hecker acknowledged his 1999 confession in an interview conducted jointly by WWL-TV and the British newspaper The Guardian.[29][30] Hecker had confessed to committing "overtly sexual acts" with at least three underage boys in the late 1960s and 1970s and revealed his close relationships with four others until the 1980s.[29] In September 2023, a grand jury indicted Hecker on charges of aggravated kidnapping, aggravated rape, aggravated crimes against nature, and theft.[31] This led to Hecker turning himself in.[31] He was booked, but entered a plea of not guilty.[31] His bail bond was set at $800,000,[31] though it was reported in January 2024 that he could not pay the bond, and remained in jail.[32] It was also revealed that while being investigation for a separate child sexual abuse case in December 2020, Hecker confessed in a legal deposition that he still looked at child pornography.[32] In April 2024, a new search warrant was issued that allowed police to seize more documents related to the investigation against Hecker, though Hecker himself was determined, shortly before this warrant was issued, to be mentally unfit to stand trial due to short-term memory loss,[33][34] but a report found that Hecker's mental health indicated he could eventually recover from this condition, and become once again mentally fit to stand trial.[35][34]

In October 2023 the archdiocese of New Orleans finally acknowledged that V.M. Wheeler, an attorney and church benefactor who had died that year after having been ordained a deacon despite the church receiving a report of earlier child abuse, had been a credibly accused child molester, after his victim received a substantial financial settlement and more than ten months after he pleaded guilty to child molestation. The victim said about the delay "They can't even do something as simple as put somebody on the list who admitted it".[36] In December 2022, Wheeler was sentenced to five years probation,[37] but died from pancreatic cancer in April 2023.[38]

In December 2023, it was revealed that the Archdiocese's bankruptcy case would drag into 2024. No solid plan for either compensating victims or determining when to end the bankruptcy had been presented by the end of 2023,[39] and the case continued in 2024.[40]

A woman named Lisa Friloux came forward to the archdiocese in March 2024 with complaints about sexual misconduct by a priest, Gilbert Enderle. In April, Enderle was "reassigned" to a location in Missouri operated by the Redemptorist order, of which he was a member. Around the same time, Louisiana state police served a search warrant in an investigation into whether the archdiocese once ran a concealed sex trafficking ring.[41] The warrant claims that some victims were assaulted in a swimming pool after they were told to "skinny dip," and that other victims were shared among priests through a system of "gifts" that the victims were instructed to pass along to other clergymen as a signal that the victim was a fitting target for sexual abuse.[42]

In August 2024 a judge appointed a business-turnaround expert to find out the status of the church's and its creditors' different proposed restructuring plans; to review costs already incurred, about $40m; and to determine if the church had the "financial wherewithal" to "reorganize and continue as a going concern".[43] The following month a committee representing survivors proposed that church-affiliated organizations and insurers should pay over $1bn to settle claims; the archdiocese in response counter-proposed to pay $62.5m.[44]

Bishops

[edit]Bishops of Louisiana and the Two Floridas

[edit]- Luis Ignatius Peñalver y Cárdenas (1795–1801), appointed Archbishop of Guatemala

- Francisco Porró y Reinado (disputed,[45] 1801–1803), then appointed Bishop of Tarazona in Spain

- Louis-Guillaume DuBourg (1815–1825), appointed Bishop of Montauban and later Archbishop of Besançon in France

- – Joseph Rosati (coadjutor bishop 1823–1825, apostolic administrator 1826–1829); resigned as coadjutor bishop 1826, appointed first Bishop of St. Louis 1827

Bishops of New Orleans

[edit]- Leo-Raymond de Neckere (1830–1833)

- – Auguste Jeanjean (appointed in 1834; resigned before assuming office)

- Antoine Blanc (1835–1850), elevated to Archbishop

Archbishops of New Orleans

[edit]

- Antoine Blanc (1850–1860)

- Jean-Marie Odin (1861–1870)

- Napoléon-Joseph Perché (1870–1883)

- Francis Xavier Leray (1883–1887)

- Francis Janssens (1888–1897)

- Placide-Louis Chapelle (1897–1905)

- James Blenk, S.M. (1906–1917)

- John W. Shaw (1918–1934)

- Joseph F. Rummel (1935–1964)

- John P. Cody (1964–1965), appointed Archbishop of Chicago (elevated to Cardinal in 1967)

- Philip M. Hannan (1965–1989)

- Francis B. Schulte (1989–2002)

- Alfred C. Hughes (2002–2009)

- Gregory M. Aymond (since 2009)

Former auxiliary bishops

[edit]- Gustave Augustin Rouxel (1899–1908)

- John Laval (1911–1937)

- Louis Abel Caillouet (1947–1976)

- Harold R. Perry, SVD (1966–1991)

- Stanley Joseph Ott (1976–1983), appointed Bishop of Baton Rouge

- Robert William Muench (1990–1996), appointed Bishop of Covington and later Bishop of Baton Rouge

- Dominic Carmon, SVD (1993–2006)

- Gregory Michael Aymond (1997–2000), appointed Coadjutor Bishop and later Bishop of Austin and Archbishop of New Orleans

- Roger Paul Morin (2003–2009), appointed Bishop of Biloxi

- Shelton Joseph Fabre (2007–2013), appointed Bishop of Houma-Thibodaux and later Archbishop of Louisville

- Fernand J. Cheri, OFM (2015–2023), died in office

Other priests of this diocese who became bishops

[edit]- Thomas Heslin, appointed Bishop of Natchez in 1889

- Cornelius Van de Ven, appointed Bishop of Natchitoches in 1904

- Jules Jeanmard, appointed Bishop of Lafayette in Louisiana in 1918

- Robert Emmet Tracy, appointed Auxiliary Bishop of Lafayette in Louisiana in 1959 and later Bishop of Baton Rouge

- Joseph Gregory Vath, appointed Auxiliary Bishop of Mobile-Birmingham in 1966

- Gerard Louis Frey, appointed Bishop of Savannah in 1967 and later Bishop of Lafayette in Louisiana

- William Donald Borders, appointed Bishop of Orlando in 1968 and later Archbishop of Baltimore

- John Clement Favalora, appointed Bishop of Alexandria in 1986 and later Bishop of Saint Petersburg and Archbishop of Miami

- Thomas John Rodi, appointed Bishop of Biloxi in 2001 and later Archbishop of Mobile

- Joseph Nunzio Latino appointed Bishop of Jackson in 2003

- Dominic Mai Luong, appointed Auxiliary Bishop of Orange in 2003

- John-Nhan Tran, appointed Auxiliary bishop of Atlanta in 2022

Landmarks

[edit]St. Louis Cathedral is located on Jackson Square in the French Quarter of New Orleans. It was originally built in 1718, shortly after the founding of the city. The church building was destroyed by fire several times before the current structure was built between 1789 and 1794 during Spanish rule. During renovations to the cathedral between 1849 and 1851, St. Patrick's Church, the second-oldest parish in the city, served as the pro-cathedral of the archdiocese.

Parishes

[edit]The 108 parishes of the archdiocese are divided into 10 deaneries.

Schools

[edit]The Archdiocese of New Orleans has five colleges and over 20 high schools. Many of the parishes operate primary schools .

Previously Catholic schools were racially segregated. In 1962 there were 153 Catholic schools; that year the archdiocese began admitting black students into schools that did not admit them; that year about 200 black children attended the archdiocese's Catholic schools previously not reserved for black children. The desegregation occurred two years after public schools had integrated. Bruce Nolan of The Times Picayune stated that because Catholic schools had a later desegregation, white liberal and African-American groups faced disappointment but that the integration had not produced as intense of a backlash.[46]

Seminaries

[edit]- Notre Dame Seminary – New Orleans

- Saint Joseph Seminary College – Saint Benedict

Ecclesiastical province of New Orleans

[edit]See also

[edit]- List of the Roman Catholic dioceses of the United States#Ecclesiastical province of New Orleans

- Category:Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans

References

[edit]- ^ "Home". Our Lady of the Isle. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ^ a b "United States Bankruptcy Court – Eastern District of Louisiana – Court Docket – Case 20-10846 (The Roman Catholic Church of the Archdiocese of New Orleans)". Donlin Recano. September 13, 2024. New material added as required.

- ^ a b c Points, Marie Louise. "New Orleans." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. November 19, 2017

- ^ Nolan, Charles E. "A Brief History of the Archdiocese of New Orleans." Archived October 4, 2006, at the Wayback Machine 2001 May.

- ^ Finney, Peter. "Devastation." The Clarion Herald. 2005 Oct. 1. Vol. 44, No. 9.

- ^ Chuck Colbert (November 25, 2009). "Dioceses major contributors to repeal same-sex marriage". National Catholic Reporter. Kansas City, Missouri. Retrieved November 29, 2009.

- ^ "Welcome to the Public Campaign Finance Page for the State of Maine". Archived from the original on September 11, 2012. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- ^ a b "There Are 81 Accused Clergy Members From The Archdiocese Of New Orleans, LA". Louisiana Priest Abuse – Accused Priest List & Settlements. AbuseLawsuit.com (Report). August 8, 2022. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Statement". New Orleans Saints. January 24, 2020.

- ^ a b "New Orleans Saints confirm staff helped Archdiocese during sex abuse revelations". WGN-TV. January 25, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ VARGAS, RAMON ANTONIO (December 12, 2020). "George Brignac, disgraced former New Orleans deacon, indicted on child rape charge". NOLA.com. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

- ^ LaRose, Greg (June 30, 2020). "Accused deacon George Brignac breaks back in jail fall, lawyer says". WDSU. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

- ^ Perlstein, Mike; Vargas, Ramon Antonio (July 1, 2020). "Disgraced deacon George Brignac dies while awaiting 1980s child rape trial".

- ^ Hammer, David; VARGAS, RAMON ANTONIO (December 16, 2020). "Monster in our midst: Timeline of George Brignac's abuse in New Orleans area churches". NOLA.com.

- ^ "Archdiocese of New Orleans files for bankruptcy". The Catholic World Report. May 1, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c VARGAS, RAMON ANTONIO (April 30, 2020). "Archdiocese of New Orleans to file bankruptcy; Aymond meets with area priests". NOLA.com.

- ^ a b Curth, Kimberly (May 6, 2020). "Attorneys for alleged victims of church sex abuse respond to Archdiocese of New Orleans bankruptcy filing". www.fox8live.com.

- ^ a b "Abuse victims challenge legitimacy of Archdiocese bankruptcy claim". wwltv.com. August 20, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ a b c VARGAS, RAMON ANTONIO (May 19, 2020). "Leader of New Orleans archdiocese ministry's board resigns after filing clergy sex abuse lawsuit". NOLA.com.

- ^ a b VARGAS, RAMON ANTONIO. "New Orleans priest admits to 'sin' with teen student, still wants retirement payments restarted". Nola. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ^ HAMMER, DAVID; VARGAS, RAMON ANTONIO (November 5, 2020). "Church paid New Orleans sex abuse victim $100,000 then waited two years to investigate the priest". Nola.

- ^ "Priest abuse victims question if Archdiocese properly investigated, referred cases to Vatican". wwltv.com. November 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Hammer, David (August 19, 2020). "New Orleans' archdiocese adds priest to credibly accused list after almost 2 decades of allegations". WWLTV News. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- ^ Hammer, David (February 7, 2022). "Former New Orleans priest dies under Air Force investigation, amid new evidence of coverup". WWL-TV. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c VARGAS, RAMON ANTONIO; Hammer, David (October 23, 2020). "Rev. Pat Wattigny, Louisiana priest accused of sexual abuse, arrested in Georgia". Nola.

- ^ a b Vargas, Ramon Antonio (June 20, 2023). "Revealed: New Orleans archdiocese concealed serial child molester for years". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Vargas, Ramon Antonio (June 20, 2023). "A New Orleans priest confessed to abusing children. He returned to work and was never charged". The Guardian.

- ^ Vargas, Ramon Antonio (May 9, 2024). "'It wasn't a big deal': secret deposition reveals how a child molester priest was shielded by his church". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Hammer, David (August 23, 2023). "Priest admits sexual abuse of teens to WWL-TV". WWL-TV. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ Vargas, Ramon Antonio; Hammer, David (August 23, 2023). "In a first, New Orleans priest accused of abusing minors admits wrongdoing". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Mackel, Travers (September 13, 2023). "Former priest Lawrence Hecker pleads not guilty, bond set". WDSU. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ a b Hammer, David (January 19, 2024). "Jailed priest admitted under oath that he still looks at child porn". WWL-TV. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ Payne, Daniel (April 25, 2024). "Louisiana police obtain new search warrant in New Orleans Archdiocese abuse investigation". Catholic News Agency. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ a b Hammer, David; Vargas, Antonio (April 25, 2024). "Retired priest Lawrence Hecker declared incompetent for rape trial, for now". WWL. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- ^ Hammer, David; Vargas, Antonio (April 23, 2024). "US priest accused of raping teen in 1975 not fit to stand trial, psychiatrists say". The Guardian. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- ^ Vargas, Ramon Antonio; Hammer, David (October 17, 2023). "Why did church take so long to admit New Orleans deacon was a child abuser?". The Guardian.

- ^ Hunter, Michelle (December 6, 2022). "Suspended St. Francis Xavier deacon gets 5 years probation in child molestation case". The Times-Picayune/The New Orleans Advocate. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ "Former Metairie deacon convicted of child sex abuse, has died". WWL-TV. April 6, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ Killion, Aubry (December 21, 2023). "New Orleans Archdiocese bankruptcy case drags into 2024, sex abuse survivors ready for closure". WDSU. Retrieved December 22, 2023.

- ^ Riegel, Stephanie (March 26, 2024). "Ruling on abuse 'lookback window' has implications for Archdiocese of New Orleans bankruptcy". NOLA.

- ^ Vargas, Ramon Antonio (August 19, 2024). "She accused a New Orleans priest of sexual assault. The church quietly moved him out of state". The Guardian.

- ^ Mustian, Jim (May 1, 2024). "Expanding clergy sexual abuse probe targets New Orleans Catholic church leaders". Associated Press.

- ^ Hammer, David (August 22, 2024). "Judge appoints outside expert to review $40m New Orleans church bankruptcy". The Guardian.

- ^ Vargas, Ramon Antonio; Hammer, David (September 14, 2024). "New Orleans Catholic church offers $62.5m after abuse victims seek $1bn". The Guardian.

- ^ "Bishops of Archdiocese". St. Louis Cathedral. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

Penalver, First Bishop... DuBourg, Second Bishop, after an interval marked by rebellion against ecclesiastical authority... de Neckere, Third Bishop

- ^ Nolan, Bruce (November 15, 2010). "New Orleans area Catholic schools integrated 2 years after the city's public schools". The Times Picayune. Archived from the original on November 16, 2010. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Archdiocese of New Orleans". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Archdiocese of New Orleans". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

External links

[edit]- Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans Official Site

- Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans (archdiocese-no.org) at the Wayback Machine (archive index)

- Nolan, Charles E. A History of the Archdiocese of New Orleans Archived October 4, 2006, at the Wayback Machine May 2001

- Archdiocesan Statistics. Archived October 11, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Catholic Charities of New Orleans.

- The Clarion Herald, the official newspaper of the Archdiocese of New Orleans.

- John and Kathleen DeMajo. Gallery of New Orleans Churches, including numerous Catholic Churches.

- Vargas, Ramon Antonio (November 29, 2023). "'You're only as sick as your secrets': New Orleans clergy abuse bankruptcy is uniquely acrimonious". The Guardian.

The first of a three-part series exploring how the archdiocese of New Orleans's bankruptcy stands apart from other cases of its kind.