Théophile Steinlen

Théophile Alexandre Steinlen (November 10, 1859 – December 13, 1923), was a Swiss-born French Art Nouveau painter and printmaker. He was politically engaged and collaborated with anarchist and socialist press.[1]

Biography

[edit]Born in Lausanne, Switzerland,[2] Steinlen studied at the University of Lausanne before taking a job as a designer trainee at a textile mill in Mulhouse in eastern France. In his early twenties he was still developing his skills as a painter when he and his wife Emilie were encouraged by the painter François Bocion to move to the artistic community in the Montmartre Quarter of Paris.[3] Once there, Steinlen was befriended by the painter Adolphe Willette who introduced him to the artistic crowd at Le Chat Noir that led to his commissions to do poster art for the cabaret owner/entertainer, Aristide Bruant and other commercial enterprises.

In the early 1890s, Steinlen's paintings of rural landscapes, flowers, and nudes were being shown at the Salon des Indépendants. His 1895 lithograph titled Les Chanteurs des Rues was the frontispiece to a work entitled Chansons de Montmartre published by Éditions Flammarion with sixteen original lithographs that illustrated the Belle Époque songs of Paul Delmet. Five of his posters were published in Les Maîtres de l'Affiche.

His permanent home, Montmartre and its environs, was a favorite subject throughout Steinlen's life and he often painted scenes of some of the harsher aspects of life in the area. His daughter Colette was featured in much of his work.[4] In addition to paintings and drawings, he also did sculpture on a limited basis, most notably figures of cats that he had great affection for as seen in many of his paintings.[3] Steinlen included cats in many of his illustrations, and even published a book of his designs, Dessins Sans Paroles Des Chats.[5]

Steinlen became a regular contributor to Le Rire and Gil Blas magazines plus numerous other publications including L'Assiette au Beurre and Les Humouristes, a short-lived magazine he and a dozen other artists jointly founded in 1911.[6] Between 1883 and 1920, he produced hundreds of illustrations, a number of which were done under a pseudonym so as to avoid political problems because of their harsh criticisms of social ills. His art influenced the work of other artists, including Pablo Picasso.[7][2]

Théophile Steinlen died in 1923 in Paris and was buried in the Cimetière Saint-Vincent in Montmartre. Today, his works can be found at many museums around the world including at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia. and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., United States. A stone monument by Pierre Vannier was created for Steinlen in 1936; it is located in Square Joël Le Tac in Paris.[8]

Selected works

[edit]-

Cocorico (1896)

-

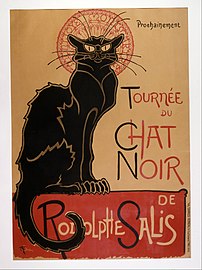

La tournée du Chat Noir de Rodolphe Salis (1896)

-

Mothu et Doria (1896-1900)

-

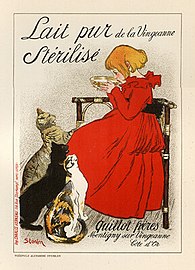

Lait Pur Stérilisé de la Vingeanne (1897)

-

Café à Léon (1921)

-

25 Juin 1916 - Journée Serbe (1916)

References

[edit]- ^ Fau-Vincenti, Véronique (2020-08-11), "STEINLEN Théophile, Alexandre", Le Maitron (in French), Paris: Maitron/Editions de l'Atelier, retrieved 2023-03-18

- ^ a b "Théophile Alexandre Steinlen". Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ a b "Steinlen". Denison. Denison Museum. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ Asimakis, Magdalyn (2 November 2017). "War, Socialism, and Cats: Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen's Political Artistic Practice". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ Price, Matlack (February 1924). "Illustrator, Posterist, Lithographer: The Graphic Arts Lose Théophile Alexandre Steinlen". Arts & Decoration. Nineteen: 35. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ "La Marseillaise / The Mobilisation". Graphic Arts Collection. Princeton University. 13 May 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ Miller, Brian (20 October 2010). "Denison revives prints in three-pronged show Exhibit of tobacco print ads also shown". The Advocate.

- ^ "Square Joël Le Tac (ex-Constantin Pecqueur)". Mon Paris. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

External links

[edit]- Steinlen.net - A collection of more than 2,500 Steinlen images

- Théophile Steinlen in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website

- 1859 births

- 1923 deaths

- Art Nouveau painters

- Art Nouveau illustrators

- 19th-century French painters

- French male painters

- 20th-century French painters

- 20th-century French male artists

- French poster artists

- Artists from Lausanne

- Swiss emigrants to France

- Swiss printmakers

- 20th-century French printmakers

- People of Montmartre

- University of Lausanne alumni

- People from Alsace

- 19th-century French male artists

- Swiss anarchists

- French anarchists