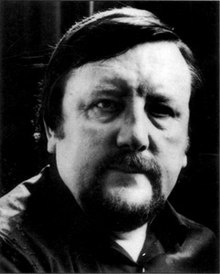

Bob Shaw

Bob Shaw | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Robert Shaw 31 December 1931 Belfast, Northern Ireland |

| Died | 11 February 1996 (aged 64) Warrington, England |

| Occupation | Novelist, structural engineer, aircraft designer, journalist |

| Period | 1954–1995 |

| Genre | Science fiction |

Robert Shaw[1] (31 December 1931 – 11 February 1996) was a science fiction writer and fan from Northern Ireland, noted for his originality and wit. He won the Hugo Award for Best Fan Writer in 1979 and 1980. His short story "Light of Other Days" was a Hugo Award nominee in 1967, as was his novel The Ragged Astronauts in 1987.

Life

[edit]Shaw was born and raised in Belfast, the eldest of three sons of a policeman.[2] He learned of science fiction at about 11 years old when he read an A. E. van Vogt short story in an early edition of Astounding Science-Fiction magazine. During the Second World War, American troops passed through Northern Ireland and often left their used SF magazines behind at Smithfield Market, where they were available for locals.[3] He later described the experience as being more significant and long-lasting than taking LSD.[4] He attended Belfast College of Technology.[5] In 1950 he joined the group Irish Fandom, which also included another Northern Irish science fiction writer James White, and met at the house of Walt Willis on Upper Newtownards Road, Belfast.[6] The group was influential in the early history of science fiction fandom and produced fanzines Hyphen and Slant; Shaw contributed material to both.[2] Shaw acquired the nickname "BoSh" during this period.[7] His first professional science fiction short story was published in 1954,[8] followed by several others.

He gave up writing and went with his first wife Sadie (née Sarah Gourley) and their son and two daughters to live in Canada from 1956 to 1958. His novel Vertigo is set in Alberta, and Orbitsville's limitless grasslands may have been influenced by this period in his life.[9] Originally trained as a structural engineer, he worked as an aircraft designer for Short and Harland, then as science correspondent to The Belfast Telegraph from 1966 to 1969, and as publicity officer for Vickers Shipbuilding (1973–1975), before starting to write full-time. In April 1973, during the Troubles, Shaw and his family moved from Northern Ireland to England, where he produced most of his published work: first to Ulverston, then to Grappenhall in Warrington. After Sadie died suddenly in 1991, Shaw lived alone there for some years.

Shaw nearly lost his eyesight through illness, and suffered migraine-induced visual disturbances throughout his life. Speculative treatments of seeing, and references to eyes and vision, appear in some of his works.[7] He was known as a drinker, and at one stage considered himself an alcoholic.[10] He was quoted in 1991 as saying: "I write science fiction for people who don't read a great deal of science fiction." He married American Nancy Tucker in 1995 and went to the US to live with her, then returned to England in the last months of his life. Shaw died of cancer on 11 February 1996.[11]

Works

[edit]Shaw is the author of "Pilot Plant" (May 1966) which first appeared in New Worlds (May 1966) and "Light of Other Days" (August 1966), the story that introduced the concept of slow glass, through which the past can be seen. Shaw sold this story to Analog editor John W. Campbell, who liked it so much Shaw wrote a sequel for him, "Burden of Proof", in May 1967. The original story was written in four hours, but after years of planning.[12] Shaw expanded on the concept in the novel Other Days, Other Eyes, and the concept was adopted by the Marvel Comics/Curtis Magazines anthology magazine Unknown Worlds of Science Fiction.

His work ranged from essentially mimetic stories with fantastic elements far in the background (Ground Zero Man) to van Vogtian extravaganzas (The Palace of Eternity). Orbitsville and its two sequels deal with the discovery of a habitable shell completely surrounding a star, and the consequences for humanity. Orbitsville won the 1976 British SF Association Award.[7] Later in his career he wrote the Land and Overland trilogy (The Ragged Astronauts, The Wooden Spaceships and The Fugitive Worlds), set on a system of worlds where technology has evolved with no metals. Like Philip K. Dick, he explored the nature of perception in his fiction.[13]

Shaw was known in the fan community for his wit. Following his early membership of Irish Fandom, with Walt Willis, and James White, he always remained a keen reader of and contributor to fanzines. At the British science fiction convention Eastercon, he delivered a humorous speech (often part of his famous series known by the tongue-in-cheek label of "Serious Scientific Talks") for many years; these were eventually collected in The Eastercon Speeches (1979) and A Load of Old Bosh (1995), which included a similar talk at the 1979 Worldcon in Brighton, 37th World Science Fiction Convention. For these he won the 1979 and 1980 Hugo Award for Best Fan Writer. He wrote The Enchanted Duplicator with Walt Willis in 1954, a piece of fiction about science fiction fandom modelled on John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress.[7]

Bibliography

[edit]Novels and collections of short stories

[edit]- Night Walk (1967). Banner.

- The Two-Timers (1968). New York: Ace Books.

- The Palace of Eternity (1969). New York: Ace Pub. Corp.

- The Shadow of Heaven (1969). New York: Avon.

- One Million Tomorrows (1970). New York: Ace Books.

- Ground Zero Man (1971). New York: Avon Books. – revised edition published as The Peace Machine (1985). London: Gollancz.

- Other Days, Other Eyes (1972). New York: Ace Books.

- Tomorrow Lies in Ambush (1973). London: Gollancz. – collection.

- The Orbitsville trilogy

- Orbitsville (1975). London: Gollancz.

- Orbitsville Departure (1983). New York: DAW Books.

- Orbitsville Judgement (1990). London: Gollancz.

- A Wreath of Stars (1976). London: Gollancz.

- Cosmic Kaleidoscope (1976). London: Gollancz. – collection.

- Cosmic Kaleidoscope (1977). New York: Doubleday – collection.

- Medusa's Children (1977). New York: Doubleday.

- The Warren Peace saga

- Who Goes Here? (1977). London: Gollancz. – reissued in 1988 with a short story The Giaconda Caper.

- Warren Peace (1993). London: Gollancz. – reissued in 1994 as Dimensions

- Ship of Strangers (1978). London: Gollancz – collection.

- Vertigo (1978). London: Gollancz. reissued in 1991 as Terminal Velocity by the same publisher.

- Dagger of the Mind (1979). London: Gollancz.

- The Ceres Solution (1981). London: Granada.

- Galactic Tours (1981, with David A. Hardy).

- Courageous New Planet (1981). Birmingham Science Fiction Group – limited-edition chapbook.

- A Better Mantrap (1982). London: Gollancz – collection.

- Fire Pattern (1984). London: Gollancz.

- Messages Found in an Oxygen Bottle (1986). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Nesfa. – collection. Bound double format with Between Two Worlds by Terry Carr

- Land and Overland trilogy

- The Ragged Astronauts (1986). London: Gollancz.

- The Wooden Spaceships (1988). London: Gollancz.

- The Fugitive Worlds (1989). London: Gollancz.

- Killer Planet (1989). London: Gollancz.

- Dark Night in Toyland (1989). London: Gollancz – collection.

- Overload (1995). Birmingham Science Fiction Group – limited-edition chapbook.

Nonfiction

[edit]- The Best of the Bushel (1979)

- The Eastercon Speeches (1979)

- How to Write Science Fiction (1993)

- A Load of Old BoSh (1995) (includes The Eastercon Speeches)

Selected short stories

[edit]- "Light of Other Days" (1966)

- "Skirmish on a Summer Morning" (1976)

- "Unreasonable Facsimile" (1974)

- "A Full Member of the Club" (1974)

- "The Silent Partners" (1959)

- "The Element of Chance" (1969)

- "The Gioconda Caper" (1976)

- "An Uncomic Book Horror Story" (1975)

- "Deflation 2001" (1972)

- "Waltz of the Bodysnatchers" (1976)

- "A Little Night Flying" ("Dark Icarus") (1975)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Nicholls 1981

- ^ a b Lyons & O'Malley-Younger 2008, p. 195

- ^ Fennell, Jack (2014). Irish Science Fiction. Oxford University Press. p. 157. ISBN 9781781381199.

- ^ Stableford 1995, p. 22

- ^ Reginald 1974, p. 240

- ^ "Oblique House - Fancyclopedia 3".

- ^ a b c d "Cloud Chamber 118 – D. Langford". Ansible.co.uk. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "Title: Aspect".

- ^ Lyons & O'Malley-Younger 2008, p. 197

- ^ Priest, Christopher. "Bob Shaw | Christopher Priest, author". Christopher-priest.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "Bob Shaw Obituary". The Independent. 17 February 1996. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Ashley 2005, p. 286

- ^ Lyons & O'Malley-Younger 2008, p. 200

Sources

[edit]- Ashley, Mike (2005). Transformations: the story of the science-fiction magazines from 1950 to 1970. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-769-7.

- Lyons, Paddy; O'Malley-Younger, Alison (2008). No country for old men: fresh perspectives on Irish literature (1st ed.). Peter Lang. p. 195. ISBN 978-3-03911-841-0. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- Nicholls, Peter, ed. (1981). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. St Albans: Granada Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-586-05380-8.

- Reginald, Robert (1974) [1970]. Contemporary Science Fiction Authors (2nd ed.). Wildside Press LLC. ISBN 1-4344-7858-0. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- Stableford, Brian (1995). Algebraic fantasies and realistic romances (1st ed.). Wildside Press LLC. ISBN 0-89370-283-8. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

Further reading

[edit]- Langford, David (2005). The Sex Column and Other Misprints. Wildside Press LLC. p. 31. ISBN 9781930997783.

External links

[edit]- 1931 births

- 1996 deaths

- 20th-century novelists from Northern Ireland

- Science fiction writers from Northern Ireland

- Hugo Award-winning fan writers

- Male novelists from Northern Ireland

- Male short story writers from Northern Ireland

- Writers from Belfast

- 20th-century short story writers from Northern Ireland

- Chapbook writers

- 20th-century male writers from Northern Ireland